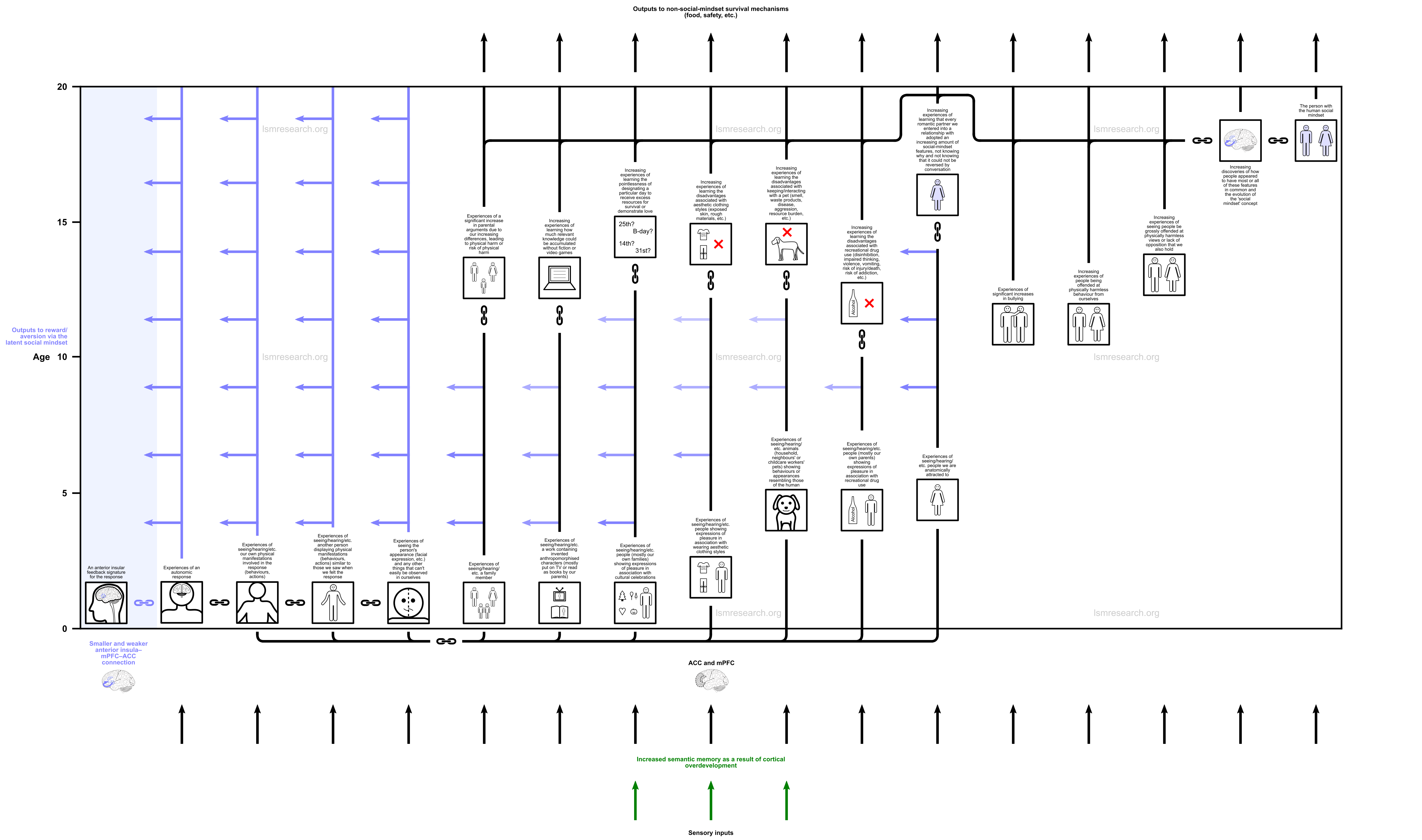

With every experience we have, we learn more things (at a higher rate) that regulate our innate survival mechanisms than those that become attached to brainstem responses (our latent social mindset).

This means that it is set in stone from birth that we will ‘learn’ our way out of the social mindset at some point as one outruns the other, and this is subjectively how it feels.

Early childhood

Social-mindset associations (episodic memories linked to brainstem-response signatures) are initially built from very rudimentary knowledge/experiences, for example, the appearance of one’s own behaviour during an emotion and a similarly appearing behaviour in someone else.

Since as an infant, one does not have much other knowledge, this initially sets the stage for almost any given person to resemble oneself and trigger these associations.

At birth, we have no knowledge and start at an equal playing field, but a widening gap between the two sets of mechanisms immediately forms.

Since this is small to begin with, we come to adopt a few features of the social mindset in childhood, though always to a lesser degree than those around us. Since we also start off gaining knowledge at a higher rate, we very quickly prefer to socialise with adults or others who are knowledgeable.

Mid-childhood

By age 11, we have adopted certain social-mindset features to some degree, however our rates are still different, and we continue to veer away from the trajectory of other people as we learn more about others than they become attached to our latent social mindset.

This continually results in a) re-appraising certain social-mindset features in a non-social lens and b) only wanting to socialise with a more and more select group that resembles us more closely in worldview and knowledge.

Both of these features lead to increasing friction with family and peers. This can take the form of arguments over our behaviour with family or bullying with peers.

In a case of a positive-feedback loop, this fuels the fire, since the friction leads to more individual-survival strategies adopted within the context of a reduced rate of social-mindset associations being added. For example, the episodic memories of family, which used to be attached to brainstem responses (the social mindset), become far outcompeted by new memories that merely regulate innate survival mechanisms.

Mid-to-late teenage years

By mid-teenage years, our will to socialise with most people has been heavily outcompeted by new knowledge learnt through experiences with those people and a lack of understanding at the now rapidly increasing social-mindset features that people our age express.

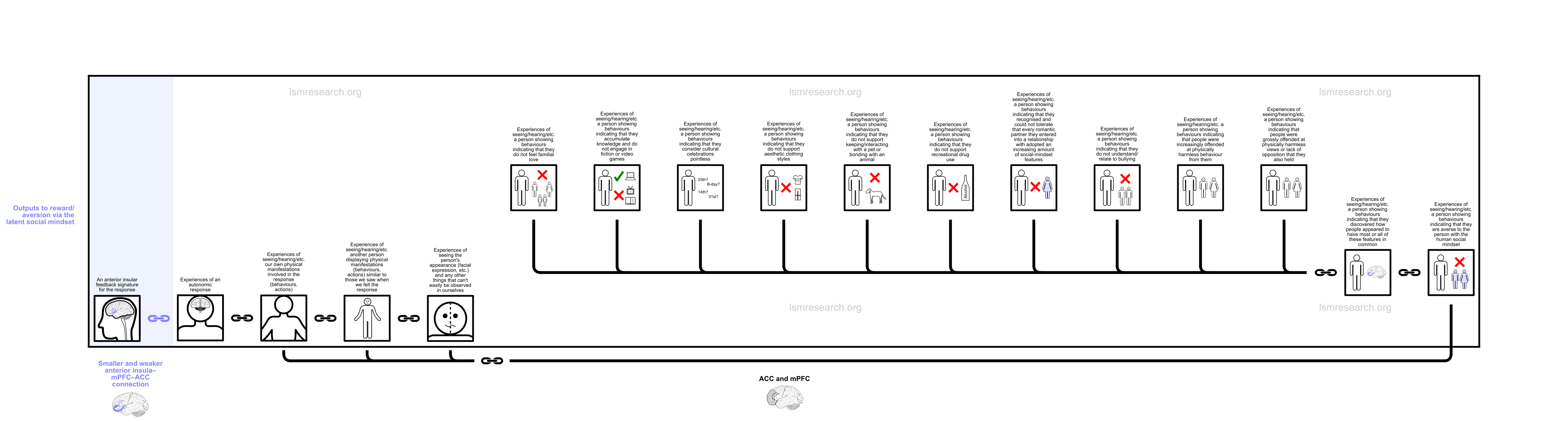

Rather than it being simply a case of anxiety or anhedonia, not only do we not feel the pleasure and reward those with the social mindset feel towards features such as pet-keeping or fashion styles, we also do not feel the sadness or outrage they feel towards a perceived social tragedy or political injustice. Their brainstem-response-attached episodic memories progressively do not trigger emotional brainstem responses in ourselves, and emotional brainstem responses progressively do not characterise other people or phenomena. We lack empathy for a perceived tragedy, and we also lack schadenfreude or pleasure from perceived suffering. We lack positive or negative emotion in response to their social-mindset triggers.

As discussed on Features of the social mindset, the social mindset leads people to feel strong pleasure at acts that physically harm and go against the innate survival centres, but it also leads them to feel heavy scorn or outrage at acts that do not physically harm or go against the innate survival centres. We lack both the support for the individually harmful things they like and the opposition for the individually harmless things they hate. Both of these phenomena lead those with the social mindset to feel confusion and anger towards us, our views and our behaviours. For the same reason, we begin to feel confusion towards them, their views and their behaviours. All of these things give us further reason to not interact with those with the social mindset and to isolate.

By late teenage years, we begin to learn the commonalities between most social-mindset features, and eventually, all of the memories of the human features become associated with a single concept – the person with the human social mindset. Whenever we see a person exhibit a strong feature of the human social mindset, we immediately know that the person has the typical human social mindset and has the potential to engage in most other features of the human social mindset.

Given the prevalence rates of our lack of the social mindset, this makes some 99.99% of people in the world unable to meaningfully trigger our latent social mindset (or ‘unrelatable’), with the 1 out of roughly 7,500 who remain also secluding themselves away for the exact same reason.

Diagrams

Sections

The following sections provide detailed accounts of how we progressively began to see social-mindset features over time.

The sections contain many views that may offend some social-mindset sensibilities, however they are included for clinical and neuroscientific relevance, to aid in understanding how we think. Many of the excerpts are also from a time of confusion and frustration before we understood the mechanism of the social mindset. Try not to take them personally, and do not attribute intent to harm where there isn’t any.

Some quotes in each section are paraphrased for presentation.

- Cultural celebrations

- Recreational drug use

- Body modifications/cosmetics/jewellery

- Fashion/aesthetic clothing styles

- Pets/animal-bonding

- Fiction

- Theism/spirituality/belief in a general ‘higher power’

- Musical social-mindset associations

- Psychogenic obesity/’comfort eating’

- Familial love

- Friend love

- Romantic love

- Sexual social-mindset associations

- Educational institutions

- Valuation of money

- Susceptibility to advertising

- Susceptibility to psychotherapy/counselling

- Threat-proxy features

- Taboos/laws

- Politics

- Basal social-mindset features

- Emotion

- The social mindset as a whole

- Unconscious thought appropriation

- Autism community