Studies have pointed to a nuanced but generally diametric relationship between schizophrenia and autism.

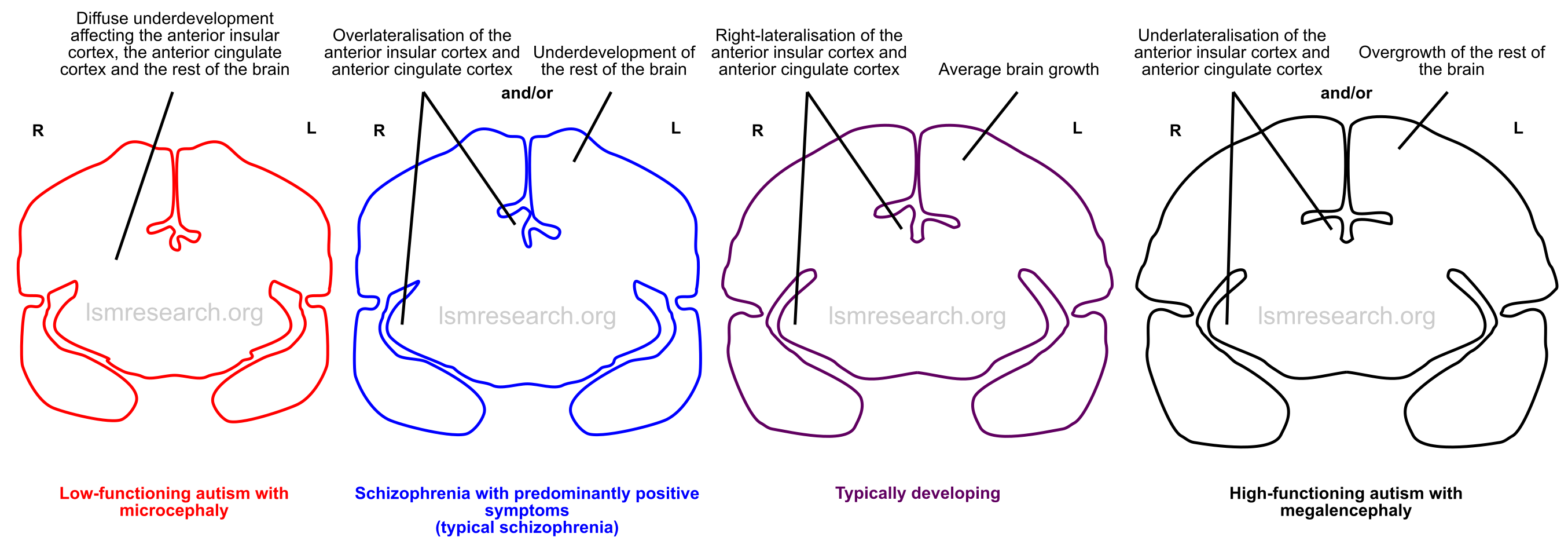

For example, microcephaly has been associated with schizophrenia, while megalencephaly is often associated with autism spectrum disorder.[1][2]

Schizophrenia has been linked to deletions (at 1q21 and 22q11.21) or duplications (at 16p11.2 and 22q13.3) at several unstable chromosomal loci, while autism has been linked to opposing duplications or deletions at the same loci.[2]

The opposing nature of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and the symptoms of autism has also been discussed.[3]

This page gathers the evidence on the relationship between the two conditions and arrives at explanations for the symptoms of schizophrenia in line with the neurology, features and genetics of the social mindset and a conclusion on the diametric relationships that are indicated.

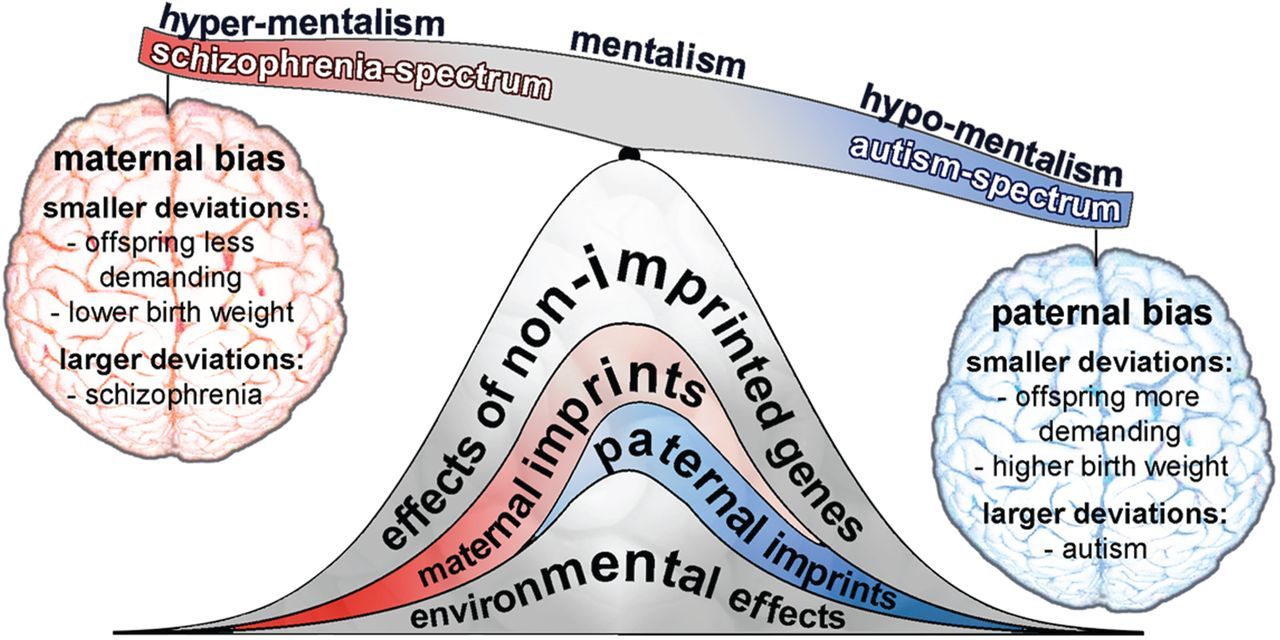

Imprinted brain theory

One of the first theories to extensively highlight the diametric symptom presentations between schizophrenia and autism was the imprinted brain theory, formulated in 2008 by Christopher Badcock and Bernard Crespi.[1]

Badcock and Crespi theorised that a diametric relationship arises from autism involving relative underdevelopment of social cognition, manifesting in symptoms such as deficits in shared attention and literal thinking, and schizophrenia involving relative overdevelopment of social cognition, manifesting in symptoms such as over-attribution of intent (delusions of paranoia and conspiracy).[1]

The theory also posits that genomic imprinting of certain genes contributes to this relationship by affecting brain growth.

Genomic imprinting is a phenomenon that evolved in therian/placental mammals and flowering plants (where the endosperm has a placenta-like function for the seed[4]). It refers to parent-specific silencing of certain genes in the germ cells, mostly through DNA and histone methylation. This leads to the offspring only expressing these genes from one particular parent.[5]

As of 2020, around 100 genes were known to be imprinted in humans.[6][7] Imprinted genes are generally found in clusters on the genome.[8]

The main theory for imprinting is the kinship theory, which states that it occurs due to the differing interests of mothers and fathers in multiple-paternity species of these taxonomic groups.[4][5]

Natural selection favours the persistence of both parents’ genes, but in species such as placental mammals, a single mother may be raising the young of multiple fathers. In these cases, it is in the fathers’ interests to suppress genes that diminish resource acquisition by their offspring from the mother, so that his offspring can acquire the most resources, but it is in the mother’s interest to suppress genes that cause her offspring to hoard too many resources, so that all of her offspring have an equivalent chance to survive. This extends from alterations in placental absorption ability to alterations in the neurology of the offspring.[4][5]

Source: [9]. Licence: CC-BY-4.0.

Positive symptoms

Positive symptoms of psychotic spectrum disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, etc.) are those that indicate an abnormal presence of a feature. They include paranoia, delusions and hallucinations.[10]

Neurology

My research has found that positive symptoms of psychotic spectrum disorders are associated with differences in the social-mindset brain regions and the rest of the brain that are an exaggeration of those of typical individuals and inverse to those of myself or those reported in autism spectrum disorder.

Studies have generally found an association between a proportionally large right anterior insula and right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) compared to the left, within the context of relative underdevelopment of the rest of the brain, and positive symptoms of psychotic spectrum disorders.

The anterior insula and ACC are right-lateralised in typical individuals and underlateralised in myself and those with autism spectrum disorder, and growth of the rest of the brain is average in typical individuals and increased in ourselves and some of those with autism spectrum disorder.

Anterior insular cortex

- A 2008 study[11] found that the right insula was more active in those with schizophrenia experiencing hallucinations.[12]

- A 2012 meta-analysis found a significant correlation between reduced grey-matter volume in the left insula and severity of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia.[13]

- A 2006 study found that those with schizophrenia had reduced volume of the left anterior insula, which correlated with bizarre behaviour.[14]

- A 2012 study found that males with schizophrenia had larger right insulae than left insulae relative to normal.[15]

Anterior cingulate cortex

- A 2003 study found that the perigenual ACC, especially the left perigenual ACC, was significantly smaller in females (but not males) with schizophrenia.[16]

- A 2008 study found that the left ACC was smaller in those with bipolar disorder.[17]

- A 2009 study found that males with bipolar disorder with a first psychotic episode had increased thickness in the right subcallosal ACC.[18]

- A 1995 study found a non-significant correlation between reduced left ACC size and severity of hallucinations in schizophrenia.[19]

- A 2008 study found that the left cingulate cortex was significantly smaller in those with schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms (but not those with primary negative symptoms) compared to healthy controls.[20]

Rest of the brain

Reduction of cortical grey matter in much of the brain is often seen in schizophrenia.[21][22][23]

Reduced hippocampal size is a consistent finding in schizophrenia.[24] The hippocampus is one of the only regions of the brain to undergo continued neurogenesis in adulthood.[25]

The dopamine and glutamate hypotheses of schizophrenia state that increased dopamine transmission (the primary neurotransmitter of the mesolimbic pathway) and decreased glutamate transmission (the primary neurotransmitter of most of the brain) are involved in the pathology. Glutamatergic transmission in the rest of the brain tends to inhibit the mesolimbic pathway.[26]

Dilatation of the ventricles (due to increased cerebrospinal-fluid build-up) is found in around 80% of those with schizophrenia.[27] A 2020 study found that ventricular dilatation in a mouse involving the schizophrenia-associated deletion in 22q11.2 was related to defective motility of the motile cilia (fluid-beating appendages) in the ependyma (walls) of the ventricles.[28]

Defective cilia are indicative of a loss-of-function in microtubule-related genes, which are necessary for both cilia formation and brain growth.

Genetics

A study shown below found that increased severity of positive symptoms in schizophrenia is associated with differences in the number of copies of subtypes of the Olduvai domain that are largely inverse to those associated with increased severity of social deficits in autism spectrum disorder.

Specifically, decreased CON1 copy number is associated with increased severity of positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Decreased HLS1 copy number had a similar association but with only a quarter of the effect.

Microtubule-related genes

NBPF family – CON1 and HLS1 subtypes

A 2015 study looked at the copy number of the CON1 and HLS1 Olduvai subtypes in a sample of those with schizophrenia. Both repeats were found in the normal ranges (CON1: 47–81; HLS1: 146–261). However, the schizophrenic males, on average, had fewer CON1 copies than the schizophrenic females.[29]

Decreased CON1 copy number was associated with increased severity of positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions), which was significant in those with adult-onset schizophrenia. Those with mostly positive symptoms, on average, had significantly fewer CON1 copies than controls or those with mostly negative symptoms. These effects were strongest in males, and, in addition, males with mostly positive symptoms had significantly fewer CON1 copies than males from a sample of those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[29]

Decreased HLS1 copy number had a similar significant association with increased severity of positive symptoms but with approximately a quarter of the effect of decreased CON1 copy number. HLS1 copy number was not significantly different between those with schizophrenia, controls, or those with ASD. However, those with mostly positive symptoms of schizophrenia had significantly fewer HLS1 copies than those with mostly negative symptoms.[29]

Other microtubule-related genes

Loss-of-function mutations in other microtubule-related genes have been linked to both microcephaly and psychotic spectrum disorders such as schizophrenia.

- Loss-of-function mutations in both copies of NDE1 causes microcephaly and lissencephaly.[30] Loss-of-function mutations in NDE1 have also been linked to schizophrenia.[31][32]

- Loss-of-function mutations in both copies of pericentrin (PCTN) causes microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type II.[33] Loss-of-function mutations in PCTN have also been linked to schizophrenia[34][35] and major depressive disorder.[36]

- A 2020 study found that loss-of-function mutations in CEP85L resulted in a predominantly posterior form of lissencephaly.[37] Another 2020 study found that a particular mutation in CEP85L was associated with risk of schizophrenia.[38]

RAS/MAPK pathway–related genes

The 14-3-3 family of proteins are associated with the RAF kinases of the RAS/MAPK pathway,[39] which is associated with autism with megalencephaly when overexpressed.

Underexpression of the 14-3-3 family in the prefrontal cortex has been associated with schizophrenia.[40]

The 14-3-3 genes include YWHAB, YWHAE, YWHAG, YWHAH, YWHAQ and YWHAZ.

Loss-of-function mutations in YWHAE have been associated with rare cases of schizophrenia.[41] A 2014 study found that schizophrenics with a particular mutation in YWHAE had significantly reduced left-insula volume over schizophrenics without the mutation.[42]

A 2009 study found that loss-of-function mutations in YWHAH were associated with psychotic bipolar disorder.[43] A 1999 study found an association between a tandem repeat in the 5′ untranslated region of YWHAH and schizophrenia.[44]

A 2004 study found an association between a mutation in YWHAZ and paranoid schizophrenia.[45] On the other hand, a 2019 study found that a gain-of-function mutation in YWHAZ resulted in a form of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome,[46] a RAS/MAPK pathway–related disorder associated with autism with megalencephaly. Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome is caused by gain-of-function mutations in the BRAF kinase.[47]

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is closely related to the RAS/MAPK pathway and is associated with autism spectrum disorder and megalencephaly when overactive.[48][49] It has been associated with schizophrenia when underactive.[49]

Social-mindset-related features

Given this, my research appears to offer an explanation for the persecutory and paranoid nature of positive symptoms in psychotic spectrum disorders.

In these cases, the disparity in growth of the social-mindset brain regions disproportionately affects those that respond to the sympathetic (‘fight-or-flight’) nervous system, and as such, a much higher number of phenomena both trigger and are characterised by negative brainstem responses.

In association with reductions in the rest of the brain, this appears to be within the context of reduced episodic-memory content regulating the innate survival mechanisms.

Paranoia

Paranoia is a positive symptom of schizophrenia in which a person believes other people intend to harm them when they do not.[50] This can include the false belief that they are being harassed, followed, tricked, spied on or ridiculed or that their food has been poisoned intentionally.[51]

As a result of the greater social mindset disproportionately involving signals from the sympathetic nervous system, any negative/anxious/stressful brainstem responses during the person’s lifetime will be paired with episodic memories of witnessing their own behaviours by the social mindset far more often than positive/happy ones (and this will be at a higher rate in general compared to episodic memories regulating the innate survival mechanisms).

This means that essentially any person (i.e. anything that resembles one’s own behaviours) will more often trigger episodic-memory nodes linked to negative brainstem responses than positive brainstem responses (and at a higher rate than average), and as such, when the brainstem response comes to characterise the person, the person will be more often seen to have negative intentions than positive intentions.

Querulous paranoia

Querulous paranoia is the often excessive use of litigious action against a falsely perceived threat, such as those mentioned in the above section.[51]

Querulous paranoia thus represents a heightening of the taboos/laws feature of the social mindset.

Delusions

Delusions are fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. These can include persecutory delusions (the false belief that one is being harmed or harassed), referential delusions (the false belief that certain environmental cues, gestures or comments are directed at oneself), grandiose delusions (the false belief that one has exceptional abilities, wealth or fame) and erotomanic delusions (the false belief that another person is in love with them).[10]

Delusions associated with psychosis revolve around attribution of a false human intention or a false sense of relatability to an external object. They thus represent a heightening of several social-mindset phenomena, such as the false attribution of human intention to animals or nature.

The inability for the belief to be shaken by conflicting, external evidence also affects most social-mindset phenomena, due to the fact that the brainstem response forms part of the reasoning, prediction and expectation centre of the brain (the medial prefrontal cortex), and the person cannot subjectively rationalise this effect, leading to confabulation surrounding their reason for engaging in any social-mindset feature. This is described in the Lack of subjective awareness section of Features of the social mindset, and as such, delusions represent a heightening of this lack of subjective awareness.

Persecutory delusions are explained in Paranoia; referential delusions are explained in Ideas of reference; and grandiose delusions are explained in Mood disorder and delusions of grandeur.

Ideas of reference

Ideas of reference is a positive symptom of schizophrenia in which unrelated things that are not related to oneself are seen to be about oneself or directed to oneself, such as a newsreader on TV being believed to be talking about oneself. This is usually seen to be in a negative or hostile manner.[52]

This is a reflection of the same mechanism described in Paranoia and Delusions.

Hallucinations

Hallucinations in schizophrenia are internal sensory phenomena that the person believes are external but are not. They are often negative or persecutory.[53]

This bears resemblance to the ‘consciousness’ and ‘qualia’ problems created by the social mindset.

In line with the neurology of the social mindset and the make-up of hallucinations, the source of hallucinations would be episodic memories.

It appears that, to an abnormally high degree, aspects of the external environment are related back to similarly looking environments when one experienced certain images, sounds or voices, which are associated with a brainstem response (typically a negative one in this case), and this causes the external environment to be characterised using the brainstem response as these memories are triggered.

In other words:

- a) the external environment resembles the episodic memories when these sensory phenomena occurred, which are linked to a brainstem response, which is triggered;

- b) the brainstem response comes to characterise the external environment;

- c) the external environment is believed to harbour the emotions (or brainstem responses) one felt during the episodes of the sensory phenomena.

This is similar to how during empathy, a person or animal is believed to harbour the emotions one felt during episodes of any episodic memory that resembles their behaviours.

Hallucinations represent the typical levels of internal playback of each sensory modality those without hallucinations regularly experience, such as during daydreaming, which takes place in the default mode network, where episodic memories are fetched. The often-reported high prevalence of auditory hallucinations[10][54] correlates with the ‘voice in your head’ people have in everyday life more so than images in their head, which likely has to do with the heightened human auditory memorisation ability.

Given that the source is episodic memories (which are used to create mental possibilities and predictions, including fiction), the hallucinations do not have to be familiar figures, voices or sentences but can be synthesised ones, and this is in line with the pathology.

The mechanism described under Paranoia once again explains the often persecutory nature of the hallucinations.

As such, hallucinations are in line with the heightened social mindset and its disproportionate receipt of signals from the sympathetic nervous system.

Thought insertion

The information on Neurology of the social mindset and Unconscious thought appropriation extensively details the mechanism by which externally witnessed episodic experiences can themselves come to serve as triggers of reward/aversion and essentially become one’s own thoughts and behaviour.

Thought insertion is a positive symptom of schizophrenia in which a person feels as though their thoughts are not their own. Typically, these are negative.[55]

Two first-person accounts are as follows:

‘The real “me” is not here any more. I am disconnected, disintegrated, diminished. Everything I experience is through a dense fog, created by my own mind, yet it also resides outside my mind. I feel that my real self has left me, seeping through the fog toward a separate reality, which engulfs and dissolves this self.’[55]

‘She said that sometimes it seemed to be her own thought “but I don’t get the feeling that it is”. She said her “own thoughts might say the same thing”, “but the feeling isn’t the same”, “the feeling is that it is somebody else’s.”‘[56]

The person will often not know where the thoughts come from but will recognise that they are experiencing the thoughts subjectively.[56]

This has been described as follows:

‘The patient recognises that her putatively alien thoughts are thoughts that occur within her own psychological boundaries and that the experience is therefore her experience (she has a sense of ownership). … There is a normal sense of thought ownership in thought insertion: the patients experience the thoughts as occurring in their subjectivity.’[56]

For comparison, one can view the information on The social mindset as a whole to see our accounts on how we perceive everyone around us to have thoughts that are not their own but that they perceive as their own, which bear a lot of resemblance with this account.

Given all of this, thought insertion is an example of a heightening of the unconscious-thought-appropriation mechanism of the social mindset.

Substance use disorder

Around 50% of those with schizophrenia have a substance use disorder involving alcohol or an illegal drug, while 70% are reported to have a tobacco-smoking dependence.[57]

A 2003 study found that those with schizophrenia generally report starting smoking for the same reasons as the general population, such as relaxation (80%), habit (67%) and settling nerves (52%).[58]

This is therefore in line with a heightening of the social-mindset feature of recreational drug use.

Hyperreligiosity

Hyperreligiosity is often seen in psychotic spectrum disorders such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.[59][60]

This is in line with a heightening of the theism/spirituality/’higher power’ feature of the social mindset.

Mood disorder and delusions of grandeur

Bipolar disorder involves shifts in mood that take place across days or weeks.[10] During the manic periods, the person may have delusions of grandeur, such as that they are God or that they have created something and are owed money,[61] while during the depressive periods, the person will have very low self-esteem.[10]

I hypothesise a mechanism for mood disorder that factors in the heightened social mindset.

If a person relates powerful or successful people (or nature) to themselves to a higher degree than normal (i.e. even in a lack of significant resemblance to that person/nature), they may believe they have that success or power or have links to those people (or God). In other words, they may see themselves in those people/nature.

This may cause the person to engage in activities that seem preposterous or dangerous to the people around them. This may lead to ridicule or criticism from these people. Over time, the episodic memories of this criticism will build up.

Since the person will relate the people’s ridicule and criticism to themselves to a higher degree than normal (via the respective feature on the diagram), over time, this may lead to a cumulative effect that sends them into a deep depression with low self-esteem.

During this period of low self-esteem, people are likely to relinquish their criticism and attempt to help, and the criticism and ridicule should drastically reduce. The memories of criticism from others should thus drop to a very minimal rate of increase. As the person continues to relate powerful or successful people (or nature) to themselves, and the episodic memories of this build up, this may tip the scale once more and send the person into another delusion of grandeur or episode of mania.

The reason depressive episodes last longer than manic episodes, as well as the fact that hypomanic episodes with depressive episodes (bipolar II disorder) are more common than manic episodes with ‘hypodepressive’ episodes, and the fact that unipolar depression is more common than unipolar mania,[62] will be the fact that the overlateralised social-mindset brain regions respond more to sympathetic-nervous-system signals, as described in previous sections.

Time of onset

Similarly to our loss of the social mindset, the reason psychosis or mood disorder typically has an onset in adolescence or adulthood would be because it requires a progressive disparity in episodic memories attached to brainstem responses vs. those that regulate innate survival mechanisms.

In our case, the innate survival mechanisms have the higher rates, while in the case of psychosis, the brainstem responses (especially those of the sympathetic nervous system) have the higher rate.

Other features

Language, memory and learning

Those with schizophrenia typically perform more poorly than average on all cognitive domains.[63][24]

There are often impairments in maintaining attention and characteristic impairments in verbal working memory and semantic memory. A consistent finding is described as ‘impaired ability to encode and retain verbally presented information.’[63]

IQ, as measured by standardised tests such as the Weschler Intelligence Scales, is typically below average in schizophrenia.[63]

Formal thought disorder

Formal thought disorder includes several thought-disorder symptoms that are most manifest in speech and writing. These are generally classified as positive and/or disorganised symptoms of schizophrenia.[64]

- Derailment, or flight of ideas, refers to speech or writing that continually switches to vaguely related or unrelated ideas and may appear disjointed.[64]

- Tangentiality involves drifting to unrelated topics in an answer without ever getting back to the main point at hand.[64]

- Pressured speech, or logorrhoea, refers to speech that is abnormally emphatic or rushed. The person may speak abnormally spontaneously or frequently, and answers to questions may be great in length and tangential.[64]

- Illogicality involves speech or writing that does not logically follow on, such as connections between unrelated clauses or statements or conclusions reached from a false premise.[64]

- Incoherence, word salad or schizophasia refers to speech or writing that is largely incomprehensible. Word choice may appear totally random, words may be jumbled, and sentences may not be grammatically correct (paragrammatism).[64]

- Neologisms involve the substitution of words in a sentence with new, nonsensical words or formations.[64]

- In distractible speech, the person is abnormally susceptible to changing the subject in the middle of a sentence or idea in response to a stimulus from the environment.[64]

- Clanging refers to speech or writing that is heavily based on rhymes or similarly sounding words rather than semantic meaning. This can result in the meaning being lost.[64]

- Hypergraphia, graphorrhoea[65] and graphomania all refer to forms of excessive written work that often resembles rambling.

- Poverty of content of speech refers to a lack of meaningful information in speech. The person may speak at length without imparting much real information or imparting information that could be conveyed in a few words.[64]

- Blocking, or thought blocking, involves an interruption in speech before a train of thought or idea has been completed. After a period of silence lasting from seconds to minutes, the person may indicate that they cannot remember what they were saying or had intended to say.[64]

- Perseveration refers to the repetitive referencing of a particular word, phrase or idea during the course of speech to the extent that it appears inappropriate.[64]

Poverty of content of speech, blocking and perseveration have sometimes been referred to as negative formal thought disorder[64] and assessed as negative symptoms on some diagnostic tools,[66] however they have been acknowledged as being unrelated to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[66]

Most of these features indicate a heightening of the directed-transmission-of-language feature of the social mindset.

In essence, the person has an undue and excessive expectation that other people will understand and benefit from what is currently playing through their head and transfers this into speech or writing, even where it may not be understood.

Negative symptoms

Studies commenting on the diametric relationship between schizophrenia and autism have sometimes used the term ‘psychosis’ to avoid referring to the whole schizophrenia diagnosis,[1] which includes negative symptoms.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are those that indicate an abnormal absence of a feature. They include blunted affect (reduced emotional expression), anhedonia (reduced pleasure), avolition (reduced motivation), alogia (reduced speech) and asociality.[10]

However, primary negative symptoms (those not caused by secondary factors such as dopamine-antagonistic medications or positive symptoms) are only found in a minority of those with schizophrenia.[67] They are also associated with less severe positive symptoms and lower distress.[68]

A 2010 study of a large sample found that primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia were only found in 12.9% of patients, more of whom were male than female.[67] Male sex has been repeatedly linked to the negative symptoms.[69][70][71] Another study estimated the prevalence of primary negative symptoms as 15–30%, with lower rates in first-episode patients and higher rates in older patients;[72] one study reported primary negative symptoms to be present in 37% of patients aged 45 or over.[73] Conversely, positive symptoms are known to decrease in severity with older age, which has been suggested to be due to age-related declines in dopaminergic activity.[10]

The negative symptoms of schizophrenia also effectively constitute their own recognised disorder, schizoid personality disorder (SPD). SPD’s symptoms include flattened affect, anhedonia and a lack of interest in social relationships.[10] A 2014 study found that nearly two thirds of those with SPD were male.[74] SPD also resembles some of the features of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A 2019 study found that 5.8% of adolescent males with autism spectrum disorder met criteria for SPD,[75] and a 2012 study found that 26% of an adult male and female sex-controlled sample with ASD did, twice as many of whom were male.[76]

Studies have evidenced different etiological mechanisms behind the primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to the more common positive symptoms.[29][77][78][79]

In fact, since the beginning of the diagnosis of schizophrenia, there were doubts over the unity of the positive and primary negative symptoms, and some researchers have suggested or concluded that primary negative symptoms (termed the ‘deficit syndrome’) are a separate disorder entirely.[68][80][81]

Unlike the positive symptoms, which respond to antipsychotics, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia are known to be notoriously difficult to treat, and there is no currently established treatment for them.[82][83][84] A 1997 study also found that schizophrenics with primary negative symptoms did not respond to social-skills training, in contrast to those without.[85]

Neurology

My research has found that primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia are associated with changes in the social-mindset brain regions that are in line with those of myself or those reported in autism spectrum disorder.

Studies have generally found that a proportionally small right insula and right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) compared to the left correlates with negative symptoms of schizophrenia. There are fewer studies, most likely because schizophrenia with primary negative symptoms is less common than without.

Insular cortex

- A 2012 study found that schizophrenics with predominantly negative symptoms had reduced right posterior insula volume.[86]

Anterior cingulate cortex

- A 2010 study found that reduced right rostral ACC volume correlated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[87]

- A 2013 study also found that reduced right ACC grey-matter volume correlated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[88]

A 2015 also study found that, out of a sample of those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, only those with predominantly negative symptoms had significantly reduced ACC activation in response to pleasant images in an emotional picture-rating task. This reduced activation correlated with poorer social functioning. The authors noted the evidence suggesting that this ACC hypoactivity in schizophrenia was due to negative and not positive symptoms.[79]

Reduced inferior prefrontal white-matter integrity has been found to be correlated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia,[23][89] with one study highlighting this in the right hemisphere.[90]

Strokes disrupting the connection between the right insula and ACC have been known to result in deficits in willed action. Similar symptoms have been reported after cingulotomy (cutting of the ACC white matter),[91] extending to akinetic mutism (lack of will to move or speak) in the most severe cases.[92] Ablation of the mesial frontal lobes in cats results in catatonic symptoms (bizarre postures with waxy flexibility).[93]

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is necessary for all motivated, voluntary actions, and as such, disruptions to it may result in deficits that are not restricted to the lack of the social mindset, which involves the anterior insula.

Rest of the brain

The ventricular dilatation commonly found in schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms has been reported to be not commonly found in schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms.[68][94]

Genetics

A study shown below found that increased severity of negative symptoms in schizophrenia is associated with differences in the number of copies of subtypes of the Olduvai domain that are in line with those associated with increased severity of social deficits in autism spectrum disorder.

Specifically, increased CON1 copy number is associated with increased severity of negative symptoms of schizophrenia in males.

NBPF family – CON1 subtype

In the 2015 study that looked at the copy number of the CON1 and HLS1 Olduvai subtypes in a sample of those with schizophrenia, in males, increased CON1 copy number was associated with increased severity of negative symptoms. There was no significant association in females.[29]

The authors noted that CON1 copy-number increase was associated with the symptoms that are shared between the diagnoses of autism and schizophrenia and referenced findings suggesting that the positive and primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia have independent causative mechanisms.[29]

They suggested that the minority instances of 1q21 duplications found in those with schizophrenia (where the reverse is usually true: 1q21 duplications in autism and 1q21 deletions in schizophrenia) could reflect schizophrenia cases with predominantly negative symptoms and that the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and social deficits of autism have shared causative mechanisms.[29]

Features

Given that the neurology of the social-mindset brain regions in primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia is in line with that of autism spectrum disorder, my research appears to explain the similarity of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia to the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder.

In essence, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia are symptoms of a lack of the social mindset., i.e. a reduction in the attachment of brainstem signals to episodic memories in the prefrontal cortex as they are formed.

Blunted affect

Blunted affect refers to reduced expression of emotion, such as through facial expressions, vocal intonation or gestures.[66]

This feature is assessed through displayed emotion and not self-reports of internal emotion, however reduced feeling of emotion is reflected in the negative symptom of anhedonia[66] (and the additional metric in the Brief Negative Symptom Scale ‘lack of normal distress’[95]).

This is in line with a reduction in the directed-transmission-of-language feature of the social mindset and a reduction in the ability for episodic memories to serve as both triggers of and motivations for emotional expression.

Anhedonia

Anhedonia is a reduced capacity to experience pleasure. This feature also encompasses the capacity to anticipate pleasure (which is sometimes described as the most important aspect of this feature[66]), and this has been noted as involving the same neural processes as those involved in episodic memory.[66]

This is in line with a reduction in the ability for episodic memories to serve as triggers of emotional brainstem responses.

In the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), anhedonia is rated together with asociality as ‘Anhedonia – Asociality’. This category assesses interest in leisure, sexual activities and relationships and the ability to feel pleasure from intimacy and closeness.[66]

Avolition

Avolition is reduced goal-directed activity. It is sometimes considered interchangeable with amotivation and apathy.[66]

Avolition can manifest with reduced personal maintenance, reduced motivation at school or work, reduced leisure and reduced activity in general.[66]

This appears to be in line with a reduced ability for most social-mindset features (which include social standards of personal maintenance, educational accolades and leisure) to provide reward.

Alogia

Alogia is reduced speech, especially in quantity and elaboration in response to questions. Questions are typically answered shortly or monosyllabically, in one or a few words.[66] Some questions may not be answered at all. The asker may feel the need to repeatedly prompt the person for more information.[64]

This is in line with a reduction in the directed-transmission-of-language feature of the social mindset.

Asociality

Asociality is a reduced interest in social relationships. As a primary negative symptom, it is defined as not being as a result of paranoia, delusions, hallucinations or depression.

Asociality is in line with a reduction in most of the basis of the social mindset.

Categorisation of features

Factor analyses have found that the primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia tend to correlate in two clusters:

- One cluster, termed the ‘avolition’, ‘apathy’, ‘motivation’, ‘pleasure’ or ‘experiential’ factor, includes reduced pleasure, reduced anticipatory pleasure, asociality and amotivation.[66]

- The other cluster, termed the ‘diminished expression’ or ‘expression’ factor, includes reduced quantity of speech, reduced spontaneous elaboration of speech and reduced emotional expression (such as facial expression, vocal intonation and gestures).[66]

This appears to be in line with the division between social-mindset features and features with social-mindset involvement.

In the former, the feature requires social-mindset linked episodic memories to be a source of reward or aversion. This facilitates reward from features such as money, aesthetic clothing styles or social events.

In the latter, it does not, but the experience of it being an innate reward or aversion does require being linked to the social mindset in order to be transmitted to others. This facilitates transmission of language, knowledge or music.

Increased severity of the ‘avolition’ factor is associated with a preponderance of male sex, lower social functioning in childhood and less abrupt onset of psychosis.[66]

On the other hand, increased severity of the ‘diminished expression’ factor is associated with abrupt onset of psychosis and lower cognitive functioning.[66] This appears to be related to deficits outside the social-mindset brain regions, as seen in typical schizophrenia with positive symptoms, because:

- a) deficits in the social-mindset brain regions would take out the avolition factor (social-mindset features) first and more strongly, before the diminished-expression factor (features with social-mindset involvement), and

- b) the diminished-expression features, like the features with social-mindset involvement, are much more dependent on semantic memory, which is located primarily in the temporal lobes.

Schizoid personality disorder

As mentioned under Negative symptoms, schizoid personality disorder (SPD) largely resembles the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It excludes the positive symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations.[10]

SPD has received almost no attention in scientific study in comparison to other personality-disorder diagnoses.[74][96] However, it received significant coverage in psychoanalytic literature during the mid-to-late 20th century. This attention decreased in the 1980s with the introduction of the schizotypal and paranoid personality disorders in the DSM-III[74][96] and the rise of the autism diagnosis.

Out of all currently established psychiatric disorders, the literature on SPD comes the closest to describing our lack of the social mindset. However, it does not fully correspond to the lack of the social mindset described on this site in accordance with the neurology, features and genetics.

SPD is characterised by ‘a lack of interest in social relationships, a tendency toward a solitary or sheltered lifestyle, secretiveness, emotional coldness, detachment and apathy’, and its onset is in late childhood or adolescence.[97] It is also described as being characterised by an intense internal fantasy not shared with the outside world, which has been described as the most prominent aspect and even a ‘sine qua non‘ of the disorder.[98]

On the surface, most of the literature on SPD appears as though it is vaguely attempting to describe someone like ourselves. However, if it were trying to describe the lack of the social mindset, it would contain unnecessarily vague wording, significant elements of incomplete understanding and characterisation and a number of contradictions, which are described in the following sections.

By far the largest contradiction to the lack of the social mindset is the intense internal fantasy. Fiction and fantasising is a feature of the social mindset, as it is one result of episodic memories being direct triggers of reward/aversion.

As mentioned in multiple places on Presentation and progression of our lack of the social mindset (such as under Fiction, Episodic memories as direct triggers of emotion or Romantic love), we are averse to fiction and fantasising, as we consider there to be no point in spending any time thinking about something that could not possibly be real. Regarding this criterion, my friend stated, ‘And then there’s me, not knowing what a fantasy even is and not being able to picture it.’

The only two explanations I can put forward for the prominent inclusion of this feature is that either most of those with SPD have a greater social mindset than ours, or it is an artefact of bias from assessors with the social mindset, under the assumption that the person must be generating an internal imaginary world as someone with the social mindset may do if they were depleted of social interaction. The fantasy is described as exclusively internal, so it is difficult to ascertain how it is being measured. Combined with the evidence on the site on the mechanism of the social mindset and our high conformity to the other SPD symptoms, I thus consider the latter explanation the far more likely scenario.

Like the primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia, SPD also has no established treatment (which those with SPD rarely seek), and therapy is often difficult or impossible, as those with SPD do not easily form a working relationship with a therapist.[99]

Criteria

The DSM-5 requires at least four of the following criteria to be met, to the exclusion of meeting criteria for schizophrenia or a pervasive developmental disorder, to constitute a diagnosis of SPD:[10]

- Neither desires nor enjoys close relationships, including being part of a family.

- Almost always chooses solitary activities.

- Has little, if any, interest in having sexual experiences with another person.

- Takes pleasure in few, if any, activities.

- Lacks close friends or confidants other than first-degree relatives.

- Appears indifferent to the praise or criticism of others.

- Shows emotional coldness, detachment, or flattened affectivity.

Assuming we did not meet the criteria of a pervasive developmental disorder such as autism spectrum disorder, given these criteria, we would both likely be considered to meet this diagnosis.

For myself, at least criteria 1–4, 6 and 7 would likely be considered to be met, while for my friend, at least criteria 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 would likely be considered to be met.

The ICD-10 requires the general criteria of personality disorder (F60) to be met and at least four of the following criteria to be met to constitute a diagnosis of SPD:[100]

- Few, if any, activities provide pleasure.

- Displays emotional coldness, detachment, or flattened affectivity.

- Limited capacity to express warm, tender feelings for others as well as anger.

- Appears indifferent to either praise or criticism from others.

- Little interest in having sexual experiences with another person (taking into account age).

- Almost always chooses solitary activities.

- Excessive preoccupation with fantasy and introspection.

- Neither desires, nor has, any close friends or confiding relationships (or only one).

- Marked insensitivity to prevailing social norms and conventions; if these are not followed, this is unintentional.

Assuming the general criteria were met (which would include causing ‘considerable personal distress’), given these criteria, we would both likely be considered to meet this diagnosis.

For myself, at least criteria 1–6, 8 and 9 would likely be considered to be met, while for my friend, at least criteria 1–4, 6, 8 and 9 would likely be considered to be met.

Comorbidity with Asperger syndrome

Asperger syndrome had traditionally been called ‘schizoid disorder of childhood’, and Eugen Bleuler coined both the terms ‘autism’ and ‘schizoid’ to describe withdrawal to an ‘internal fantasy’, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance.[101] (Bleuler also coined the term ‘schizophrenia‘, or ‘splitting of the mind‘, to refer to ‘[a] personality [that] loses its unity‘.[102])

In 1988, British psychiatrist Digby Tantam suggested that Asperger syndrome may confer an increased risk of developing SPD.[103]

In a 2012 study, it was found that 26% of a sample of 54 young adults with Asperger syndrome (mean age: 27; standard deviation: 3.9) also met criteria for SPD, a higher comorbidity than any other personality disorder. The other comorbidities were 19% for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, 13% for avoidant personality disorder and one female with schizotypal personality disorder.[76]

While 41% of the whole sample were unemployed with no occupation, this rose to 62% for the Asperger’s and SPD comorbid group.[76]

The authors of the study suggested that the DSM may complicate diagnosis by requiring the exclusion of a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) before establishing a diagnosis of SPD. The study found that social-interaction impairments, stereotyped behaviours and specific interests were more severe in the individuals with Asperger syndrome also fulfilling SPD criteria, against the notion that social interaction skills are unimpaired in SPD.[76]

The authors believed that a substantial subgroup of people with autism spectrum disorder or a PDD have clear ‘schizoid traits’ and correspond largely to the ‘loners’ in Lorna Wing’s 1997 classification The autistic spectrum,[104] described by Sula Wolff, which begins as follows:

‘The most subtle form of the triad [of impaired social interaction, impaired communication and restricted/repetitive behaviours and interests], described by Sula Wolff, is found in people of average, high, or outstanding ability, including fluent speech, who tend to prefer to be alone, lack empathy, and be concerned with their own interests regardless of peer-group pressures.[104]‘

A 2019 study found that 54% of a group of males aged 11 to 25 with Asperger syndrome showed significant SPD traits, with 5.8% meeting full diagnostic criteria for SPD, compared to 0% of a control with other psychiatric disorders.[75]

The authors of this study hypothesised that it was extremely likely that historic cohorts of adults diagnosed with SPD either also had childhood-onset autistic syndromes or were misdiagnosed. They stressed their view that further research to clarify overlap and distinctions between these two syndromes was strongly warranted, especially given the high rate at which high-functioning autism spectrum disorders are currently diagnosed.[75]

Some studies have questioned the validity of the SPD diagnosis and proposed that it be removed or subsumed into other diagnoses.[74][96][105]

Literature

Asociality

In SPD, the following has been described regarding social relationships:[106]

‘When someone violates the personal space of an individual with SPD, it suffocates them and they must free themselves to be independent. People who have SPD tend to be happiest when in relationships in which their partner places few emotional or intimate demands on them.

It is not necessarily people they want to avoid, but negative or positive emotions, emotional intimacy and self-disclosure.[107] Therefore, it is possible for individuals with SPD to form relationships with others based on intellectual, physical, familial, occupational or recreational activities, as long as there is no need for emotional intimacy.

Donald Winnicott explains this is because schizoid individuals “prefer to make relationships on their own terms and not in terms of the impulses of other people.” Failing to attain that, they prefer isolation.[108]‘

This appeared as a vague attempt to explain the behaviour of someone like ourselves.

The way we would describe ourselves is that we are not able to form significant relationships with people with significant social-mindset features, which happen to include empathy for most people and many other sources of human emotion such as pets. Failing to find other people with our condition, who we would be able to form meaningful relationships with, we prefer isolation.

However, it is only our own latent social mindset that allows us to desire relationships with others like us, and this is not present in most of the animal kingdom.

‘Aaron Beck and his colleagues report that people with SPD seem comfortable with their aloof lifestyle and consider themselves observers, rather than participants, in the world around them. But they also mention that many of their schizoid patients recognise themselves as socially deviant (or even defective) when confronted with the different lives of ordinary people – especially when they read books or see movies focusing on relationships.[109]

Elements of this paragraph appeared to describe ourselves slightly more accurately.

Reluctance to enter romantic relationships

In SPD, a reluctance to enter romantic relationships, due to requirements that cannot be met, has been described:[106]

‘Fairbairn notes that schizoids can fear that in a relationship, their needs will weaken and exhaust their partner, so they feel forced to disown them and move to satisfy solely the needs of the partner. The net result of this is a loss of dignity and sense of self within any relationship they enter, eventually leading to intolerable frustration and friction.

Appel notes that these fears result in the schizoid’s negativism, stubbornness and reluctance to love. Thus, a central conflict of the schizoid is between an immense longing for relationships but a deep anxiety and avoidance of relationships, manifested by the choosing of the “lesser evil” of abandoning others.[110], p. 100‘

This passage strongly resembles our attitude towards relationships, as described on the Romantic love section of Presentation and progression of our lack of the social mindset.

There is little else to clarify, other than the fact that it is of course dependent on the presence of social-mindset features in the partner, which SPD literature does not meaningfully address.

Putting on personas

Those with SPD have been described as putting on ‘personas’ in social interactions:[97]

‘Descriptions of the schizoid personality as “hidden” behind an outward appearance of emotional engagement have been recognised since 1940, with Fairbairn’s description of “schizoid exhibitionism”, in which the schizoid individual is able to express a great deal of feeling and to make what appear to be impressive social contacts yet in reality gives nothing and loses nothing.

Because they are “playing a part”, their personality is not involved. According to Fairbairn, the person disowns the part he is playing, and the schizoid individual seeks to preserve his personality intact and immune from compromise.[111] The schizoid’s false persona is based around what those around them define as normal or good behaviour, as a form of compliance.[110], p. 143‘

Personas are not something we can usually achieve or be bothered with. These descriptions most resemble the personas we would put on early on in romantic relationships, which I was not able to maintain as a practice for long before it became too draining and pointless for me.

Going through the effort of putting on a persona to interact with a person requires a perceived gain out of the social interaction (whether altruistic or harmful), which we virtually never have. Therefore, regularly voluntarily interacting whilst putting on a persona, or ‘masking’, is a manifestation of a greater social mindset than ours.

Lack of interest in sexual activity

Those with SPD have been described as appearing to be asexual, despite not having physical sexual dysfunction:[97]

‘People with SPD are sometimes sexually apathetic, though they do not typically suffer from anorgasmia. Their preference to remain alone and detached may cause their need for sex to appear to be less than that of those who do not have SPD.[112] …

[The schizoid] is often labelled asexual or presents with “a lack of a sexual identity”. Kernberg states that this apparent lack of a sexuality does not represent a lack of sexual definition but rather a combination of several strong fixations to cope with the same conflicts.[110], p. 125 …

Sex often causes individuals with SPD to feel that their personal space is being violated, and they commonly feel that masturbation or sexual abstinence is preferable to the emotional closeness they must tolerate when having sex.[112]

Significantly broadening this picture are notable exceptions of SPD individuals who engage in occasional or even frequent sexual activities with others.[112][113]‘

This appears to be a vague characterisation that roughly resembles our approach towards sex but, if applied to us, would have the same pitfalls as the rest of SPD literature.

Not tolerating violations of ‘personal space’ or ’emotional closeness’ is the default in the animal kingdom. My minimal social mindset means that only humans that are significantly like me, i.e. also lacking social-mindset features, allow me to want to form a relationship with them at all, let alone have sex with them.

The last sentence better described my friend (who has had sex), though he has also continually reduced his efforts towards relationships.

Indifference to praise or criticism

In SPD, an indifference to praise or criticism has been described:[97]

‘According to Guntrip, Klein and others, people with SPD may possess a hidden sense of superiority and lack dependence on other people’s opinions. This is very different from the grandiosity seen in narcissistic personality disorder, which is described as “burdened with envy” and with a desire to destroy or put down others.

Additionally, schizoids do not go out of their way to achieve social validation.[110], p. 60 Unlike the narcissist, the schizoid will often keep their creations private to avoid unwelcome attention or the feeling that their ideas and thoughts are being appropriated by the public.[110], p. 174‘

A social-mindset feature is to believe the opinions of others about the self. As such, it is true that neither of us are affected by praise or criticism from virtually all other people.

Envy (aggression towards non-threats to innate survival mechanisms) is also a social-mindset feature, which I have described in association with the spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies, and as such, I lack this.

The last sentence appears as a vague generalisation. Our avoidance of unwelcome attention is a reflection of the innate threat perception of other animals, where trust is not presumed and is not the default.

We do not have a reason to fear unconscious thought appropriation by others about our ideas or thoughts. Instead, this phenomenon has a history of causing us frustration, as we were unable to reason with those who had this feature (similar to how typical individuals are unable to reason with schizophrenics with thought insertion).

Reduced recreational drug use

The following has been noted about recreational drug use in SPD:[97]

‘Very little data exists for rates of substance use disorder among people with SPD, but existing studies suggest they are less likely to have substance abuse problems than the general population. One study found that significantly fewer boys with SPD had alcohol problems than a control group of non-schizoids.[114]

Another study evaluating personality disorder profiles in substance abusers found that substance abusers who showed schizoid symptoms were more likely to abuse one substance rather than many, in contrast to other personality disorders such as borderline, antisocial or histrionic, which were more likely to abuse many.[115]

American psychotherapist Sharon Ekleberry states that the impoverished social connections experienced by people with SPD limit their exposure to the drug culture and that they have limited inclination to learn how to do illegal drugs.

Describing them as “highly resistant to influence“, she additionally states that even if they could access illegal drugs, they would be disinclined to use them in public or social settings, and because they would be more likely to use alcohol or cannabis alone than for social disinhibition, they would not be particularly vulnerable to negative consequences in early use.[116]‘

Despite the accurate description of ‘highly resistant to influence’, this information depicts a greater social mindset than ours, despite it describing a lower presence of the social-mindset feature of recreational drug use.

Both of us make a point of not consuming any recreational drug, let alone an illegal one. I have never done so and never will.

Low weight

Some studies have assessed conflated samples of both individuals with SPD and individuals with Asperger syndrome. One study of individuals of this grouping found significantly low weight due to various eating difficulties:[97]

‘A 1997 study looking at the body mass index (BMI) of a sample of both male adolescents diagnosed with SPD and those diagnosed with Asperger syndrome found that the BMI of all individuals was significantly below normal. Clinical records indicated abnormal eating behaviour by some. Some would only eat when alone and refused to eat out. Restrictive diets and fears of disease were also found.[117]‘

This is strongly in line with both of our eating behaviours and low weight, as described on Other features of our lack of the social mindset.

‘It was suggested that the anhedonia of SPD may also cover eating, leading schizoid individuals to not enjoy it. Alternatively, it was suggested that schizoid individuals may not feel hunger as strongly as others or not respond to it, a certain withdrawal “from themselves”.[118]‘

This appears to be an attempt by someone with the social mindset to explain the ‘comfort eating’ feature of the social mindset. Our response to this feature is described in the respective section of Presentation and progression of our lack of the social mindset.

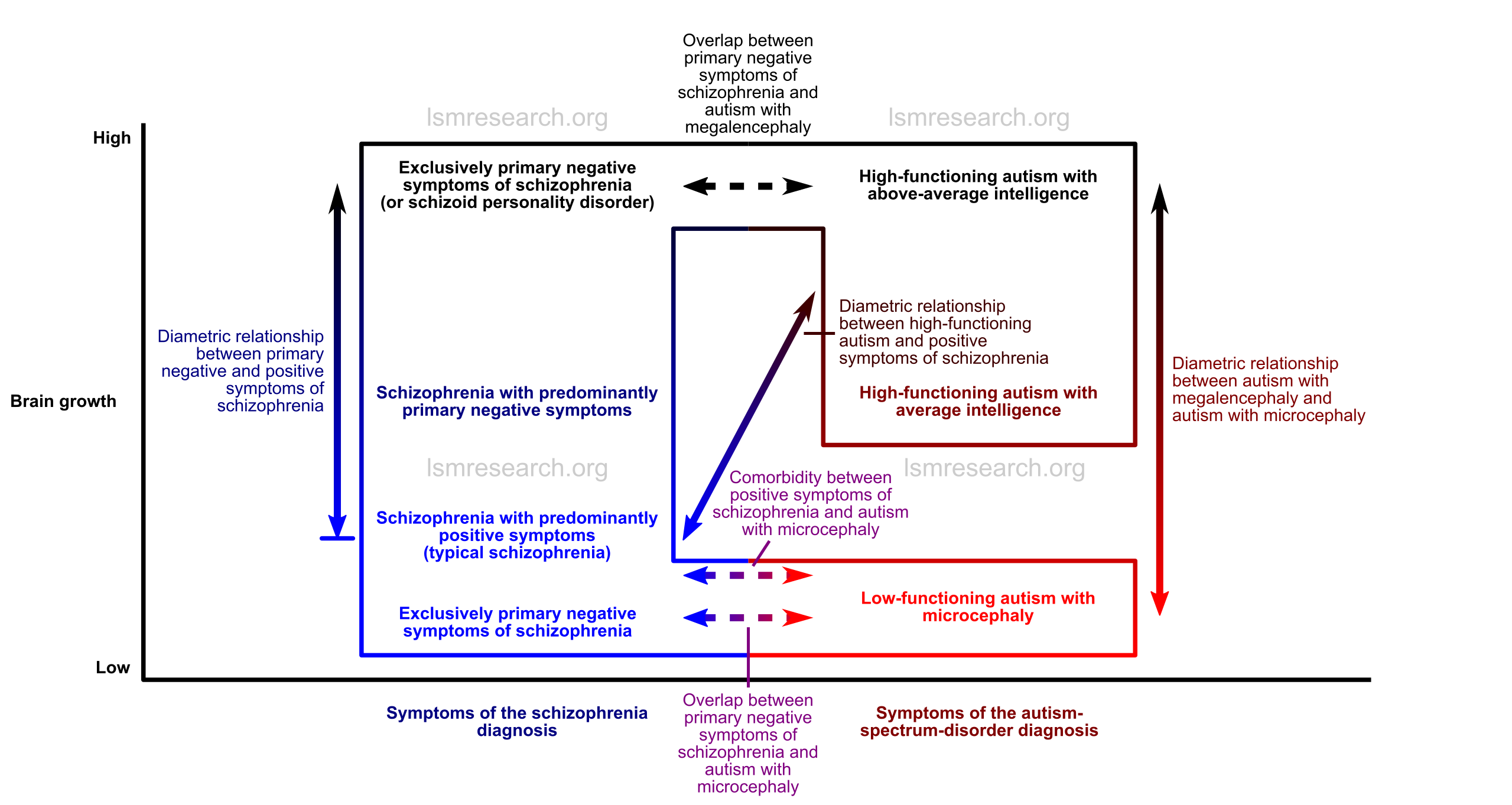

Microcephalic autism

Despite the evidence for a strong diametric relationship between the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder, such a relationship would not factor in cases of low-functioning autism due to individually rare (but collectively common) loss-of-function mutations associated with microcephaly, which has been noted by authors of some of the above studies and others.[119]

These are often (though not always) syndromic phenotypes[120] and are associated with more severe loss of function in the same genes that lead to psychotic spectrum disorders in milder cases, and some manifest with autism–psychosis comorbidity.

Examples of this include syndromes featuring cerebellar-vermis hypoplasia or Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM) (cerebellar-vermis hypoplasia, enlarged posterior fossa and often hydrocephalus) that have sometimes been reported to involve low-functioning autistic features.[121][122][123]

DWM is associated with ciliopathic loss-of-function mutations[124] (similar to those responsible for the ventricular dilatation and reduced brain growth in schizophrenia); the less severe Dandy–Walker variant has been associated with an increased rate of psychotic spectrum disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[125][126][127][128]

Another example is Waardenburg syndrome type 2E (caused by loss-of-function mutations in SOX10), which includes severe neurological abnormalities that include low-functioning autism.[129] The less severe Waardenburg syndrome type 1 (caused by loss-of-function mutations in the later-expressed PAX3) has also been associated with mood disorder/mania.[130]

If this were factored in (as a more genetic, rather than phenotypic, model), the spectrum would look more like:

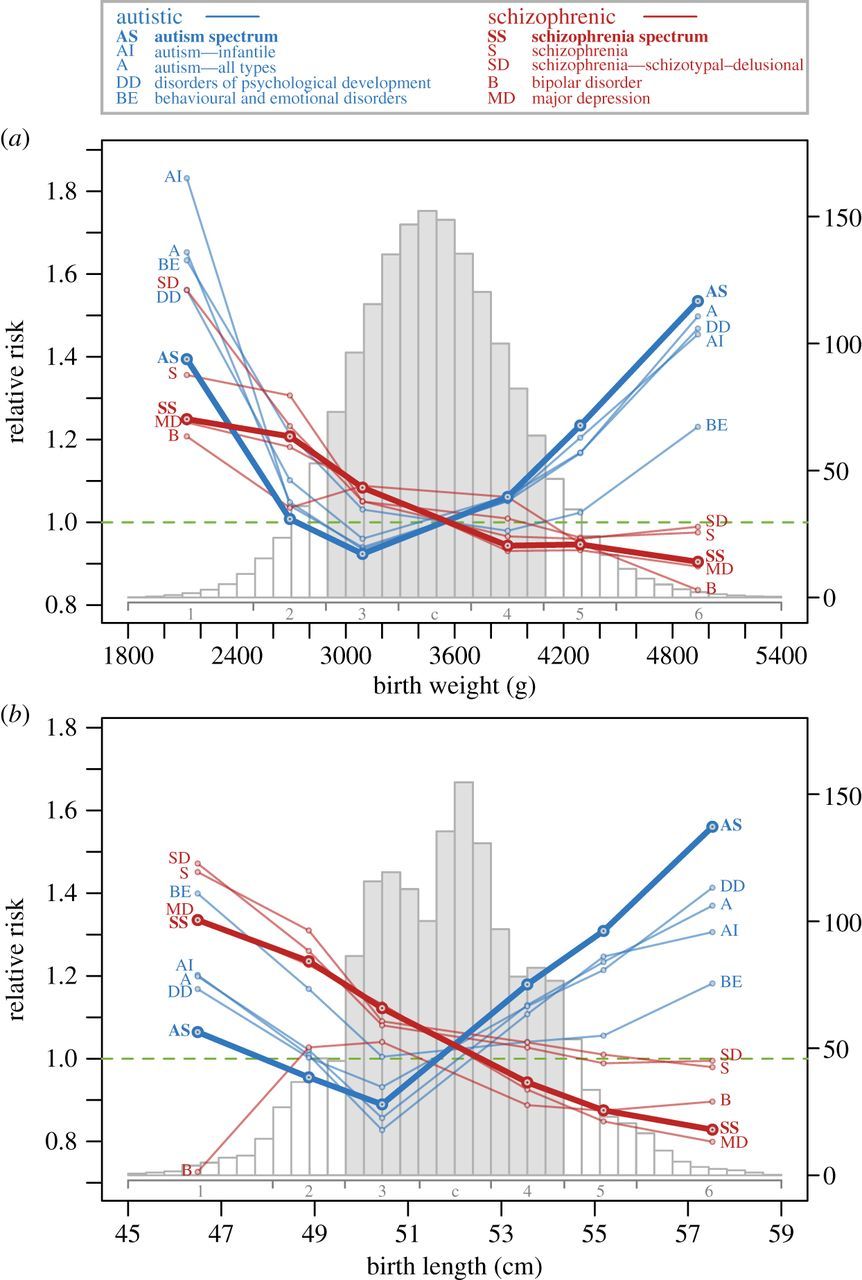

A spectrum similar to this was empirically observed and illustrated in a 2014 study on the connections between the disorders, though in association with birth weights and lengths rather than head size specifically.[9]

Source: [9]. Licence: CC-BY-4.0.

However, this spectrum also does not factor in all the significant findings, which is explained in the following section.

Conclusion

Since two groups of symptoms of a single diagnosis (schizophrenia) appear to have inverse correlations in both genetics and neurology, a proposed explanation should be put forward.

Spectrum and diametric relationships

Neurology

Neurologically, autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms are associated with underdevelopment and underlateralisation of the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex. Autism spectrum disorder is also associated with megalencephaly, however it is often present in those with average or below-average brain growth or intelligence.

On the converse, schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms (typical schizophrenia) is associated with overlateralisation of the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex. It is also associated with reduced brain growth and ventricular dilatation secondary to ciliary dysfunction, however this appears to be less in schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms.

Genetics

Genetically, this falls in line with the association between copy number of the CON1 subtype of the Olduvai domain and severity of social deficits in high-functioning autism but not low-functioning autism, severity of negative over positive symptoms of schizophrenia and brain size.

However, the symptoms of low-functioning autism with microcephaly could also be seen to have strong overlap with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, so the positive correlation between CON1 copy number and severity of autistic/negative symptoms disintegrates when approaching the lowest regions of brain growth, in which severe loss-of-function mutations in other genes that also affect the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex can result in autistic/negative symptoms despite a low contribution of the CON1 subtype of the Olduvai domain.

On the converse, reduced copy number of the CON1 subtype of the Olduvai domain and loss-of-function mutations in other microtubule-related genes are associated with increased severity or risk of positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

Overexpression or gain-of-function mutations in the RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways are also associated with autism spectrum disorder and megalencephaly.

On the converse, underexpression or loss-of-function mutations in the RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways are associated with schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms.

Features

Our condition, which aligns with severe Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism with megalencephaly, negative symptoms of schizophrenia and schizoid personality disorder, manifests with highly reduced or absent recreational drug use, valuation of money, religiosity, unconscious thought appropriation and transmission of language and above-average learning and intelligence.

On the converse, psychotic spectrum disorders with predominantly positive symptoms manifest with excessive recreational drug use, valuation of money, religiosity, unconscious thought appropriation and transmission of language and below-average learning and intelligence.

Relationships

Given this, there is a strong genetic, neurological and phenotypic diametric relationship between schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms (typical schizophrenia) and high-functioning autism with megalencephaly.

Given that the same mutations that lead to schizophrenia with positive symptoms can also lead to low-functioning autism with microcephaly, there is also a strong genetic and partial neurological and phenotypic diametric relationship between low-functioning autism with microcephaly and high-functioning autism with megalencephaly.

There is also a genetic, neurological and phenotypic diametric relationship between the positive and primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia, which is reflected in a diametric relationship between schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptoms (typical schizophrenia) and exclusively negative symptoms of schizophrenia (or schizoid personality disorder).

These relationships are illustrated in the diagrams below, which can be clicked to view full-size.

Distinctions

The differentiating factors between schizophrenia with primary negative symptoms and autism spectrum disorder include the necessary presence of positive symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, in schizophrenia[80][131] and the necessary presence of “repetitive/restrictive behaviours” in autism spectrum disorder.[10][131]

There are also sensory hyper- or hypo-sensitivities in autism spectrum disorder that, although not necessarily present in the disorder, are considered a characteristic feature of autism (and are classed under “repetitive/restrictive behaviours” in the DSM-5[10]) but not schizophrenia.

As for what causes the distinction between primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia and autistic symptoms, there may be a larger role for general voluntary-action impairment in primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to the more exclusively social impairment of autism spectrum disorder.

This may correlate more with the role of the medial prefrontal cortex in negative symptoms (so as to include avolition or, in the most extreme cases, catatonia) and the role of the anterior insula in autism (so as to include symptoms such as sensory hyper- or hypo-sensitivity).

However, the primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia and symptoms of autism largely overlap,[131][132] and in line with the evidence on the site, the diagnoses and literature may illustrate a more exaggerated distinction than that reflected in the genetics and neurology.

Autism with microcephaly is often associated with any of a wide variety of rare loss-of-function mutations. These mutations likely affect the function of the anterior insula and ventral anterior cingulate cortex within the context of much greater and more widespread dysplasia of the brain.

Consequently, what distinguishes autism with microcephaly from typical schizophrenia with positive symptoms would simply be the diffusivity and extent of dysplasia, such that the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex, usually comparatively spared compared to the rest of the brain in typical schizophrenia, are also significantly affected.

References

- ^ a b c d Crespi, Bernard; Badcock, Christopher (2008/06). "Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 31 (3): 241–261. doi:10.1017/S0140525X08004214. ISSN 1469-1825, 0140-525X.

- ^ a b Crespi, Bernard; Stead, Philip; Elliot, Michael (2010-01-26). "Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (suppl 1): 1736–1741. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906080106. ISSN 0027-8424, 1091-6490. PMID 19955444.

- ^ Crespi, Bernard J.; Ritsner, Michael S (2011). "One Hundred Years of Insanity: Genomic, Psychological, and Evolutionary Models of Autism in Relation to Schizophrenia". 163–185.

- ^ a b c Ishida, Miho; Moore, Gudrun E (2013-07-01). "The role of imprinted genes in humans". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 34 (4): 826–840. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.009. ISSN 0098-2997.

- ^ a b c Pires, Nuno D.; Grossniklaus, Ueli (2014-08-01). "Different yet similar: evolution of imprinting in flowering plants and mammals". F1000Prime Reports. 6. doi:10.12703/P6-63. ISSN 2051-7599. PMC 4126536. PMID 25165562.

- ^ "Geneimprint : Genes". Geneimprint. (Archive version from 20 June 2020.)

- ^ Allach El Khattabi, Laïla; Backer, Stéphanie; Pinard, Amélie; Dieudonné, Marie-Noëlle; Tsatsaris, Vassilis; Vaiman, Daniel; Dandolo, Luisa; Bloch-Gallego, Evelyne; Jammes, Hélène; Barbaux, Sandrine (2019-01). "A genome-wide search for new imprinted genes in the human placenta identifies DSCAM as the first imprinted gene on chromosome 21". European Journal of Human Genetics. 27 (1): 49–60. doi:10.1038/s41431-018-0267-3. ISSN 1476-5438.

- ^ Reik, Wolf; Walter, Jörn (2001-01). "Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1038/35047554. ISSN 1471-0064.

- ^ a b c Byars, Sean G.; Stearns, Stephen C.; Boomsma, Jacobus J (2014-11-07). "Opposite risk patterns for autism and schizophrenia are associated with normal variation in birth size: phenotypic support for hypothesized diametric gene-dosage effects". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1794): 20140604. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0604.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l American Psychiatric Association (2013-05-22). "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.)".

- ^ Sommer, Iris E. C.; Diederen, Kelly M. J.; Blom, Jan-Dirk; Willems, Anne; Kushan, Leila; Slotema, Karin; Boks, Marco P. M.; Daalman, Kirstin; Hoek, Hans W.; Neggers, Sebastiaan F. W.; Kahn, René S (2008-12-01). "Auditory verbal hallucinations predominantly activate the right inferior frontal area". Brain. academic.oup.com. 131 (12): 3169–3177. doi:10.1093/brain/awn251. ISSN 0006-8950.

- ^ Menon, Vinod; Uddin, Lucina Q (2010-6). "Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function". Brain structure & function. 214 (5-6): 655–667. doi:10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. ISSN 1863-2653. PMC 2899886. PMID 20512370.

- ^ Palaniyappan, Lena; Balain, Vijender; Radua, Joaquim; Liddle, Peter F (2012-05). "Structural correlates of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 137 (1-3): 169–173. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.038. ISSN 1573-2509. PMID 22341902.

- ^ Makris, Nikos; Goldstein, Jill M.; Kennedy, David; Hodge, Steven M.; Caviness, Verne S.; Faraone, Stephen V.; Tsuang, Ming T.; Seidman, Larry J (2006-04-01). "Decreased volume of left and total anterior insular lobule in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 83 (2): 155–171. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.020. ISSN 0920-9964.

- ^ Bauernfeind, Amy L.; de Sousa, Alexandra A.; Avasthi, Tanvi; Dobson, Seth D.; Raghanti, Mary Ann; Lewandowski, Albert H.; Zilles, Karl; Semendeferi, Katerina; Allman, John M.; (Bud) Craig, Arthur D.; Hof, Patrick R.; Sherwood, Chet C (2013-4). "A volumetric comparison of the insular cortex and its subregions in primates". Journal of human evolution. 64 (4): 263–279. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.12.003. ISSN 0047-2484. PMC 3756831. PMID 23466178.

- ^ Takahashi, Tsutomu; Suzuki, Michio; Kawasaki, Yasuhiro; Hagino, Hirofumi; Yamashita, Ikiko; Nohara, Shigeru; Nakamura, Kazue; Seto, Hikaru; Kurachi, Masayoshi (2003-04-01). "Perigenual cingulate gyrus volume in patients with schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study". Biological Psychiatry. 53 (7): 593–600. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01483-X. ISSN 0006-3223, 1873-2402.

- ^ Chiu, Sufen; Widjaja, Felicia; Bates, Marsha E.; Voelbel, Gerald T.; Pandina, Gahan; Marble, Joelle; Blank, Jeremy A.; Day, Josh; Brule, Norman; Hendren, Robert L (2008-01-01). "Anterior cingulate volume in pediatric bipolar disorder and autism". Journal of Affective Disorders. 105 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.019. ISSN 0165-0327.

- ^ Fornito, Alex; Yücel, Murat; Wood, Stephen J.; Bechdolf, Andreas; Carter, Simon; Adamson, Chris; Velakoulis, Dennis; Saling, Michael M.; McGorry, Patrick D.; Pantelis, Christos (2009/05). "Anterior cingulate cortex abnormalities associated with a first psychotic episode in bipolar disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 194 (5): 426–433. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.049205. ISSN 0007-1250, 1472-1465.

- ^ Noga, J. Thomas; Aylward, Elizabeth; Barta, Patrick E.; Pearlson, Godfrey D (1995-11-10). "Cingulate gyrus in schizophrenic patients and normal volunteers". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 61 (4): 201–208. doi:10.1016/0925-4927(95)02612-2. ISSN 0925-4927.

- ^ Galderisi, Silvana; Quarantelli, Mario; Volpe, Umberto; Mucci, Armida; Cassano, Giovanni Battista; Invernizzi, Giordano; Rossi, Alessandro; Vita, Antonio; Pini, Stefano; Cassano, Paolo; Daneluzzo, Enrico; De Peri, Luca; Stratta, Paolo; Brunetti, Arturo; Maj, Mario (2008-3). "Patterns of Structural MRI Abnormalities in Deficit and Nondeficit Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. PubMed Central. 34 (2): 393–401. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm097. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2632416. PMID 17728266.

- ^ Cahn, Wiepke; Pol, Hilleke E. Hulshoff; Lems, Elleke B. T. E.; Haren, Neeltje E. M. van; Schnack, Hugo G.; Linden, Jeroen A. van der; Schothorst, Patricia F.; Engeland, Herman van; Kahn, René S (2002-11-01). "Brain Volume Changes in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A 1-Year Follow-up Study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1002–1010. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1002. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ^ Haijma, Sander V.; Van Haren, Neeltje; Cahn, Wiepke; Koolschijn, P. Cédric M. P.; Hulshoff Pol, Hilleke E.; Kahn, René S (2013-09-01). "Brain Volumes in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis in Over 18 000 Subjects". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 39 (5): 1129–1138. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs118. ISSN 0586-7614.

- ^ a b Sanfilipo, Michael; Lafargue, Todd; Rusinek, Henry; Arena, Luigi; Loneragan, Celia; Lautin, Andrew; Feiner, Deborah; Rotrosen, John; Wolkin, Adam (2000-05-01). "Volumetric Measure of the Frontal and Temporal Lobe Regions in Schizophrenia: Relationship to Negative Symptoms". Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (5): 471–480. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.471. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ^ a b Tamminga, Carol A.; Medoff, Deborah R (2000-12). "The biology of schizophrenia". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2 (4): 339–348. ISSN 1294-8322. PMC 3181617. PMID 22033552.

- ^ Kang, Eunchai; Wen, Zhexing; Song, Hongjun; Christian, Kimberly M.; Ming, Guo-li (2016-9). "Adult Neurogenesis and Psychiatric Disorders". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 8 (9). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019026. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 5008067. PMID 26801682.

- ^ Howes, Oliver; McCutcheon, Rob; Stone, James (2015-2). "Glutamate and dopamine in schizophrenia: an update for the 21st century". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 29 (2): 97–115. doi:10.1177/0269881114563634. ISSN 0269-8811. PMC 4902122. PMID 25586400.

- ^ "What Links Larger Brain Ventricles and Schizophrenia?" Neuroscience from Technology Networks. 2020-02-17. (Archive version from 18 February 2020.)

- ^ Eom, Tae-Yeon; Han, Seung Baek; Kim, Jieun; Blundon, Jay A.; Wang, Yong-Dong; Yu, Jing; Anderson, Kara; Kaminski, Damian B.; Sakurada, Sadie Miki; Pruett-Miller, Shondra M.; Horner, Linda; Wagner, Ben; Robinson, Camenzind G.; Eicholtz, Matthew; Rose, Derek C.; Zakharenko, Stanislav S (2020-02-14). "Schizophrenia-related microdeletion causes defective ciliary motility and brain ventricle enlargement via microRNA-dependent mechanisms in mice". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14628-y. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b c d e f g Searles Quick, V B; Davis, J M; Olincy, A; Sikela, J M (2015-12). "DUF1220 copy number is associated with schizophrenia risk and severity: implications for understanding autism and schizophrenia as related diseases". Translational Psychiatry. 5 (12): e697. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.192. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 5068589. PMID 26670282.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - # 614019 - LISSENCEPHALY 4; LIS4". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. (Archive version from 13 November 2020.)

- ^ Doobin, David J. "The Role of NDE1 in the Pathogenesis of Microcephaly and Schizophrenia". Grantome. (Archive version from 7 October 2020.)

- ^ Kimura, Hiroki; Tsuboi, Daisuke; Wang, Chenyao; Kushima, Itaru; Koide, Takayoshi; Ikeda, Masashi; Iwayama, Yoshimi; Toyota, Tomoko; Yamamoto, Noriko; Kunimoto, Shohko; Nakamura, Yukako; Yoshimi, Akira; Banno, Masahiro; Xing, Jingrui; Takasaki, Yuto; Yoshida, Mami; Aleksic, Branko; Uno, Yota; Okada, Takashi; Iidaka, Tetsuya; Inada, Toshiya; Suzuki, Michio; Ujike, Hiroshi; Kunugi, Hiroshi; Kato, Tadafumi; Yoshikawa, Takeo; Iwata, Nakao; Kaibuchi, Kozo; Ozaki, Norio (2015-5). "Identification of Rare, Single-Nucleotide Mutations in NDE1 and Their Contributions to Schizophrenia Susceptibility". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (3): 744–753. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu147. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 4393687. PMID 25332407.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - # 210720 - MICROCEPHALIC OSTEODYSPLASTIC PRIMORDIAL DWARFISM, TYPE II; MOPD2". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. (Archive version from 7 October 2020.)

- ^ Ozel, Fatih; Direk, Nese; Ataseven Kulali, Melike; Giray Bozkaya, Ozlem; Ada, Emel; Alptekin, Koksal (2019-04). "Schizophrenia in microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type II syndrome: supporting evidence for an association between the: PCNT: gene and schizophrenia". Psychiatric Genetics. 29 (2): 57–60. doi:10.1097/YPG.0000000000000214. ISSN 0955-8829.

- ^ Anitha, Ayyappan; Nakamura, Kazuhiko; Yamada, Kazuo; Iwayama, Yoshimi; Toyota, Tomoko; Takei, Nori; Iwata, Yasuhide; Suzuki, Katsuaki; Sekine, Yoshimoto; Matsuzaki, Hideo; Kawai, Masayoshi; Thanseem, Ismail; Miyoshi, Ko; Katayama, Taiichi; Matsuzaki, Shinsuke; Baba, Kousuke; Honda, Akiko; Hattori, Tsuyoshi; Shimizu, Shoko; Kumamoto, Natsuko; Kikuchi, Mitsuru; Tohyama, Masaya; Yoshikawa, Takeo; Mori, Norio (2009-10-05). "Association studies and gene expression analyses of the DISC1-interacting molecules, pericentrin 2 (PCNT2) and DISC1-binding zinc finger protein (DBZ), with schizophrenia and with bipolar disorder". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics: The Official Publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 150B (7): 967–976. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30926. ISSN 1552-485X. PMID 19191256.