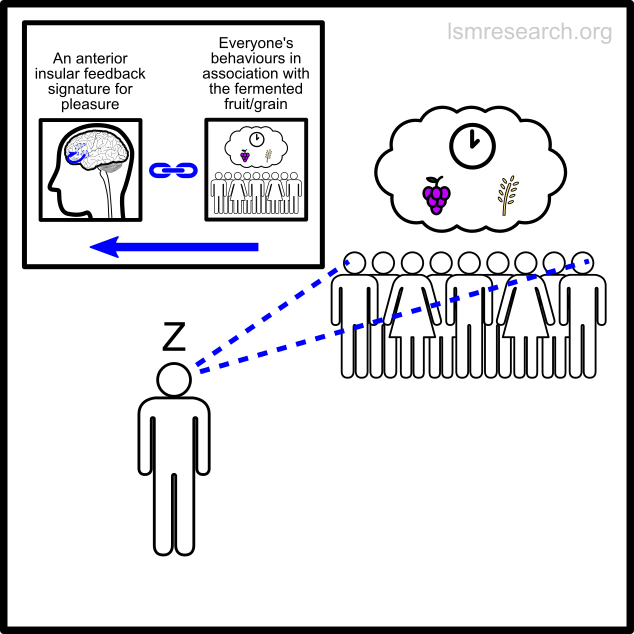

The social mindset gives rise to virtually all psychological and behavioural features known to be characteristically human, which are summarised on the homepage.

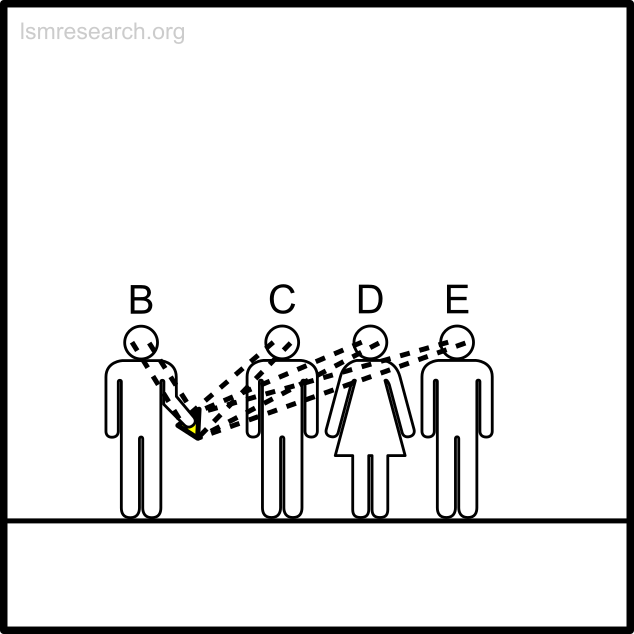

The following diagram shows a list of examples of social-mindset features that have a significant effect on modern society or otherwise help to convey the mechanism of the social mindset.

The diagram demonstrates the mechanism of appropriation of these features as sources of reward/aversion (which is further explained on Neurology of the social mindset).

The origins of some of the features themselves (which always involve multiple appropriations between many people from an original non-social-mindset root) are explained further below.

The diagram can be clicked to view full-size.

The examples listed are non-exhaustive.

Diagram

Basal social-mindset features

The features at the bottom of the diagram can be seen as ‘basal social-mindset features’.

Basal social-mindset features are those that only consist of a non-social-mindset behaviour (a behaviour that does not require previous social-mindset associations to exist), e.g., brainstem reflexes such as yawning.

Mirror self-recognition

The formative episodes for the feature of mirror self-recognition are episodes of observing one’s appearance and behaviours during any given brainstem response and then seeing the same appearance and behaviours in a reflection, which both triggers the brainstem response and results in the brainstem response characterising the reflection.

In other animals

Consistent mirror self-recognition has been demonstrated in bonobos, chimpanzees and orangutans, with inconsistent demonstration in gorillas, Asian elephants and bottlenose dolphins.[1]

Yawning contagion is present in bonobos. Its strength is higher among family and friends.[2]

Yawning contagion has also been shown for gelada baboons, including a greater strength for socially close individuals.[3]

Post-basal social-mindset features

Not independently displayed on the diagram, ‘post-basal social-mindset features’ can refer to those that closely resemble (but are not equal to) a non-social-mindset-triggered root behaviour but have become transmitted by convention. They are often perceived as universal, but nonetheless some differ in existence or characteristics among cultures.

In humans, they include hugging, kissing and applause.

Hugging

At its origin, the formative episodes for the feature of hugging would have been episodes of observing the clutching of young by a mother.

The expressions shown by the pacified child (as a result of the visually imprinted maternal-separation-anxiety mechanism) would have resembled episodic memories of one’s own expressions of pleasure, which would have triggered the associated brainstem response. This would have caused the act of clutching another individual itself to become attached as a trigger for the feeling of pleasure, causing it (or anything that resembles it) to become transmitted by convention as a social signal that one wants another to feel pacified.

Kissing

At its origin, the formative episodes for the feature of kissing would been episodes of observing premastication of certain hard foods by a mother to their infant child, who would not have had sufficient teeth to grind the food.[4][5]

The expressions of pacification shown by the child as a result of obtaining the food would have resembled episodic memories of one’s own expressions of pleasure, which would have triggered the associated brainstem response. This would have caused the act of passing food into another individual’s mouth itself to become attached as a trigger for the feeling of pleasure, causing it (or anything that resembles it) to become transmitted by convention as a social signal that one wants another to feel pacified.

In other animals

Hugging[6] and kissing[7] are also practised by bonobos. Bonobos are reported to be the only non-human animal to have been observed engaging in tongue kissing.[7]

Non-reproductive sexual behaviour among bonobos is a post-basal social-mindset feature. It is used in a way that parallels hugs in humans, being used for conflict resolution, greeting and social bonding.[8]

At its origin, the formative episodes for non-reproductive sexual behaviour in bonobos would have consisted of episodes of observing the expressions of pleasure displayed by a recipient of sex, which would have resembled episodic memories of one’s own expressions of pleasure, triggering the attached brainstem response. This would have caused the witnessed act of sex to become attached as an episodic-memory trigger for the feeling of pleasure, causing it (or anything that resembles it) to become transmitted as a social signal that one wants another to feel pacified.

The acts are transmitted as such a signal without a taboo; taboos are explained in Taboos, and the sexual taboo is explained here. Sexual taboos require that unwanted sexual advances are happening often enough to cause a high frequency of defensive aggression in the recipients, which becomes related back to one’s own defensive aggression among the social group and causes the witnessed act itself to be associated with strong social defensive aggression.

Why this does not occur in bonobos will be due to the relative lack of actual sexual attraction and subsequent penetrative vaginal sex compared to humans, in line with the limited period of visible fertility of the bonobo and the lesser social mindset facilitating fewer sexual social-mindset associations.

Social female copulatory vocalisations

Female copulatory vocalisations are calls produced by many female primate species during and after sex to attract males for sperm competition.[9] In this way, they differ from mating calls, produced by many animals before sex to advertise availability.

In bonobos, these vocalisations have acquired a social function outside purely reproductive contexts.[9]

This is also the case for humans, where the vocalisations are now used as a social signal to increase male arousal or self-esteem.[10][11]

Detached social-mindset features

Many of the features on the list have become highly detached from their non-social-mindset root.

This effect of the social mindset increases over time with increasing size and connectivity of the social group and has often only become prominent in the 20th and 21st centuries.

This detachment affects most of the commonly known features of today but can be illustrated by the two examples of recreational drug use and valuation of money.

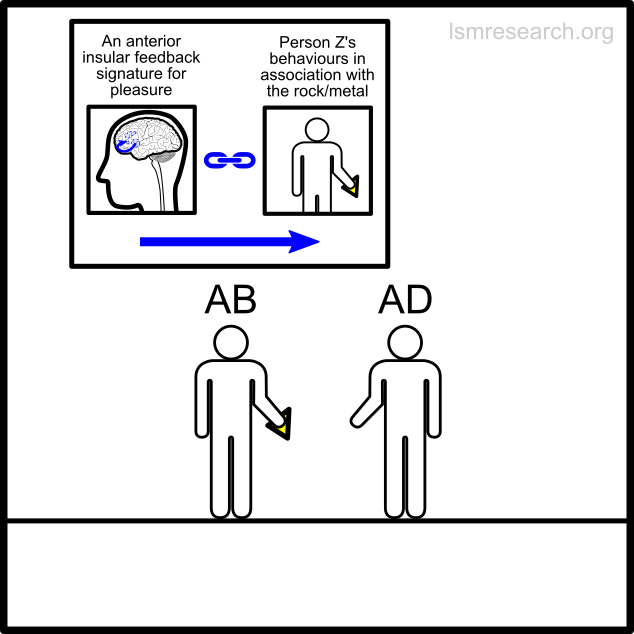

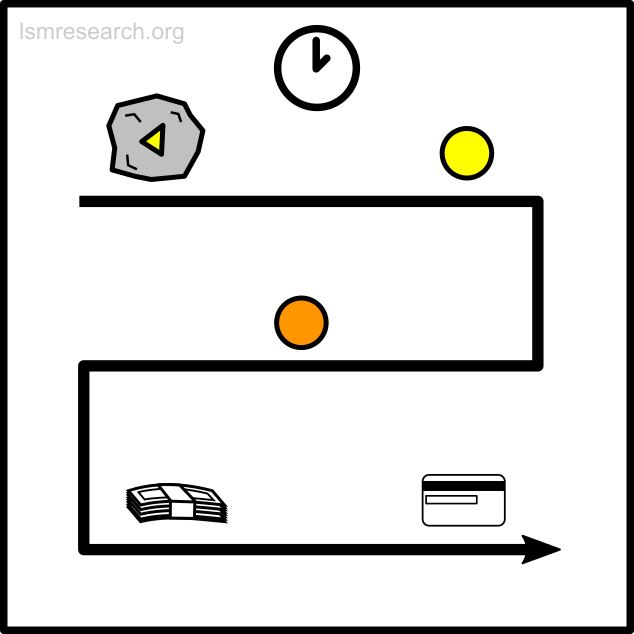

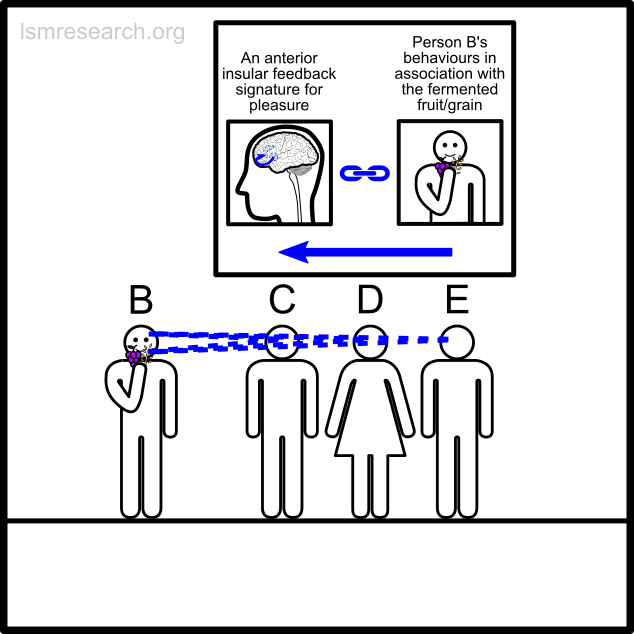

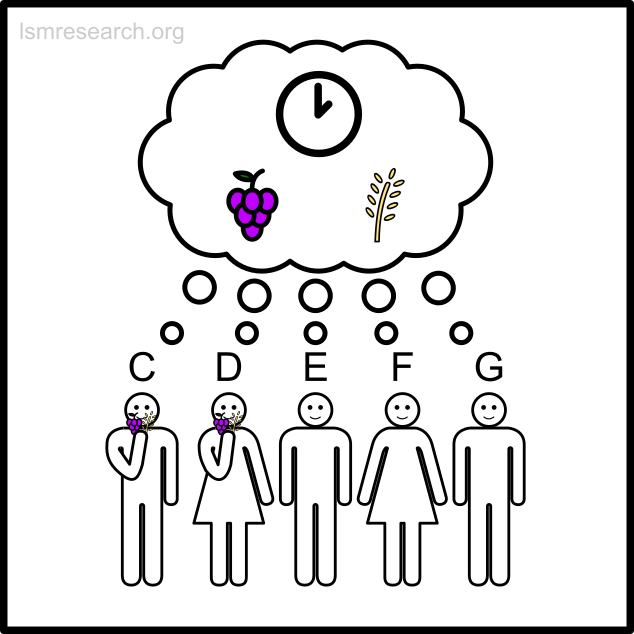

Example 1 – formation of valuation of money

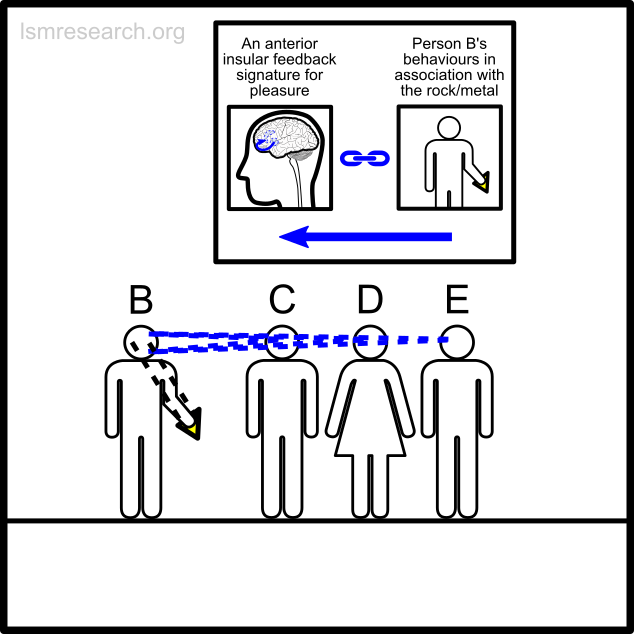

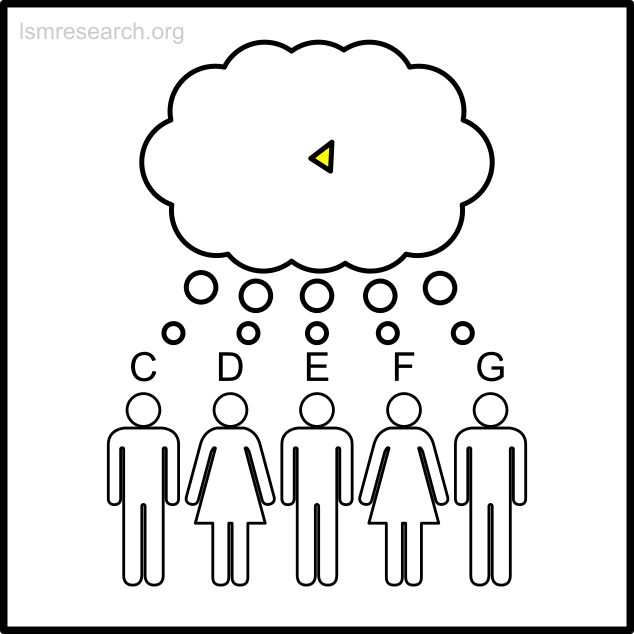

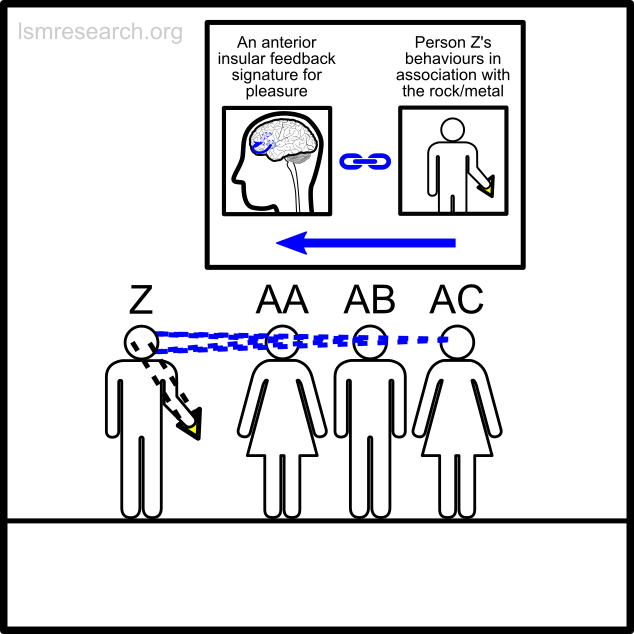

The following diagrams illustrate the formation of the social-mindset feature of valuation of money to demonstrate the detachment effect.

The alternative formative episodes for the historic and prehistoric shell money would have been a shell that stood out from the surrounding sand and stones in shape, colour or structure.

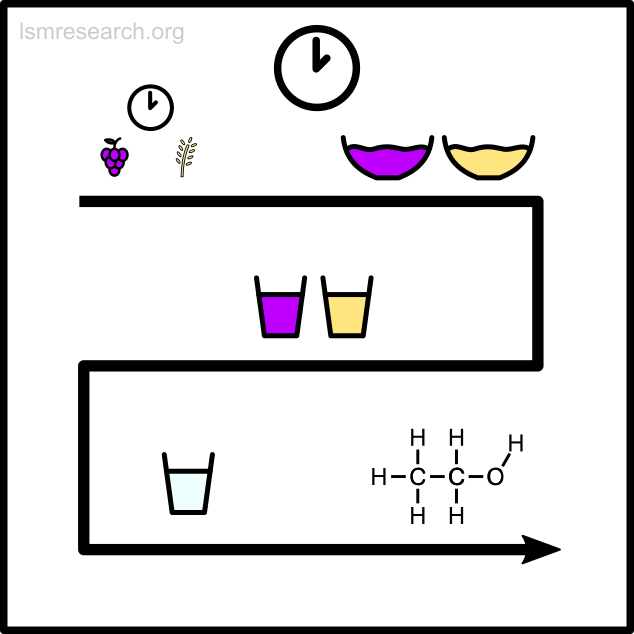

Example 2 – formation of recreational drug use

The following diagrams illustrate the formation of the social-mindset feature of recreational drug use to demonstrate the detachment effect.

The alternative formative episodes for smoking would have involved burning (or cooked) leaves emitting psychoactive fumes.

The last steps of each feature highlight the detachment effect, wherein the original, non-social reason for why the behaviour came about in its original form becomes forgotten, and a new, social reason (which is not subjectively comprehensible) is virtually all that remains.

This social reason or ‘value’ vastly inflates as the social group grows in size and connectivity until it well surpasses any resemblance to a basis outside the social group concerning just an individual’s innate survival centres. This large and progressively distorted social reason is appropriated by each generation.

Features with social-mindset involvement

There are some classically defined human features whose names cover concepts that do not require previous social-mindset associations to trigger reward or aversion. They include language, music, science, protective clothing, tools, construction, manipulation of fire and domestication of crops and livestock.

In these features, the brainstem response need not have been caused by a previous social-mindset trigger (such as feeling pleasure at clothing styles as a result of seeing someone show expressions of pleasure in association with them). Instead, it can rely solely on a non-social-mindset trigger, such as succeeding in obtaining food or avoiding pain/harm.

However, like social-mindset features, in order to be knowingly and voluntarily transmitted to others (expecting that they will understand and benefit from it as you do), the episodic memory of this non-social reward or aversion must still be added as a trigger for the social mindset.

Transmission of language and science

Semantic associations consist of visual–visual, visual–auditory, auditory–auditory or tactile (for Braille) associations.

However, directed language (whether spoken, written, signed or embossed) and teaching, expecting that another person will understand it as you do, constitute the social-mindset aspects.

The shaping of language over time from onomatopoeia (as seen in mimicking birds) to arbitrary words and pictograms to alphabets is an effect resulting from repeated transmission among the social group. Although detached in resemblance to the original sign, it does not constitute a detached social-mindset feature, since the reward/aversion from learning the sign (as seen in other animals) does not necessitate the social mindset.

See Diagram for the explanation of how language and knowledge is transmitted using the social mindset.

Pointing

Pointing is a semantic signal that would have originated from the act of reaching out to grab an object. For a much smaller object, this would have consisted of the use of the index finger and thumb.

When observing a full grab, one’s eyes would follow the hand to the eventual item. Having seen this, given an incomplete form of this act, one’s eyes would follow and predict the item that would have been grabbed. This would have resulted in a simple semantic signal indicating a particular object at the end of the pointing limb.

Like several other features with social-mindset involvement, the meaning of pointing (whether in the form of an action or a simple pictogram of a pointed finger) can be learnt by animals without the social mindset[12] but not knowingly taught by them (i.e. used with others expecting them to understand it as they do).

Transmission of music

Enjoyment from music ultimately centres on the learning and prediction confirmation involved in auditory memorisation, similar to the desire to finish a sentence with a blank, such as, ‘Happy birthday to ___.’[13]

Auditory memorisation ability is significantly heightened in mimicking birds and humans. The memorisation process is localised in the superior temporal gyrus in humans and area X of the striatum in mimicking birds. The dynamic synaptic processes in both regions are controlled by the conserved transcription factor gene FOXP2,[14] whose periodic expression generally correlates with halting synaptic growth.[15]

This heightened auditory memorisation ability is argued to have exaggerated the effect of pleasure from learning for sounds.[13]

Consequently, why pleasure from learning in mimicking birds and humans affects sound sequences in particular is most likely due to two aspects:

- a) the much higher temporal resolution, predictability and number of layers that can be memorised over a rhythmic series of smells, tastes or tactile stimuli, and

- b) the ease of reproducing the predicted sequence to aid memorisation (i.e. through the voice or an improvised instrument), unlike a colourful, rhythmic visual stimulus.

However, directed transmission of music to another individual, expecting them to perceive and enjoy it as you do (which differentiates it from birdsong), constitutes one of the social-mindset aspects of human music.

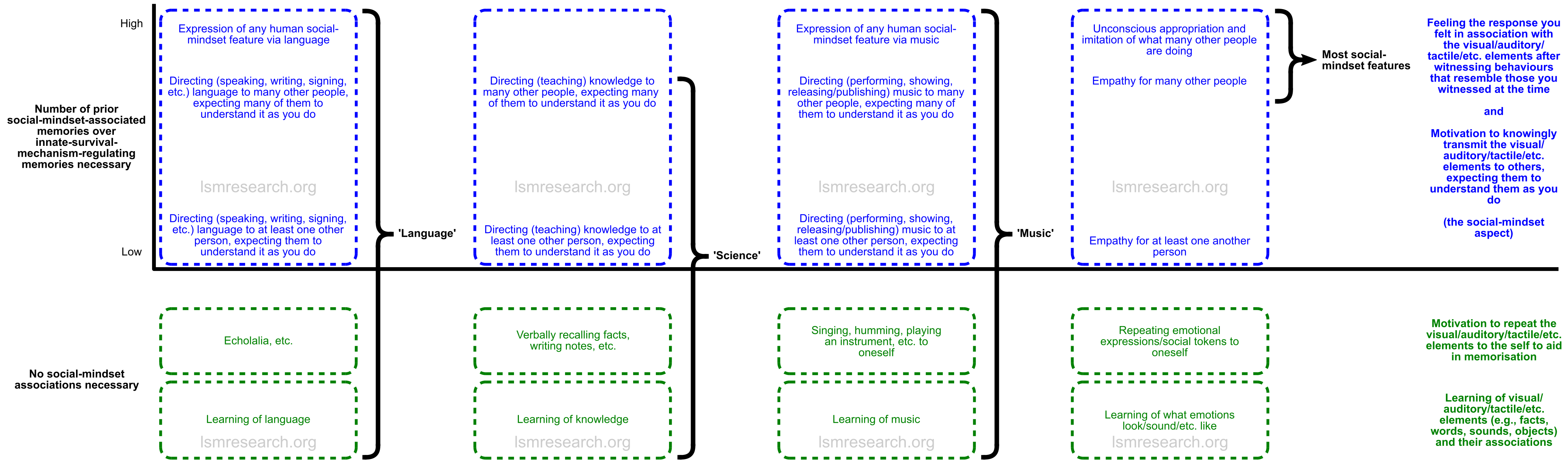

Diagram

Just like empathy or any social-mindset feature, language, knowledge and music require semantic memory. However, whilst the terms language, science and music are often considered to cover and emphasise the semantic memory needed, the term empathy is considered to cover exclusively the effect of triggering a social-mindset-associated episodic memory.

In the social-mindset features of the first diagram on this page, what is being conveyed and the ability to relate to its intended recipients requires multiple prior social-mindset-linked episodic memories in the conveying individual, since the features cannot be sources of reward or aversion without this.

Meanwhile, in order to transmit language or scientific knowledge that only regulates innate survival centres, one only requires that episodes of witnessing one’s own behaviours during the innate reward or aversion associated with the knowledge be attached to the social mindset.

When witnessing behaviours in another person similar to those one displayed prior to the knowledge having been confirmed useful, this will trigger the associated brainstem responses (neutral or negative feelings prior to an increase in pleasure), and these responses will characterise the other person (who will be perceived to be in the position prior to the increase in pleasure), leading to a desire to transmit the knowledge to the person.

Upon witnessing the other person showing behaviours indicative of having utilised, benefited from or understood the knowledge, this will match episodic memories of one’s own behaviours of having understood or benefited from knowledge, triggering the associated brainstem response (pleasure) in the self.

Essentially, learning of any of these features and repetition to the self to aid memorisation is not the social-mindset feature, whilst directed transmission of the features to at least one other person, expecting that they will understand and benefit from it as you do, constitutes the social-mindset feature.

This is what separates the broader concepts of language, science or music from the more specific concepts of the social-mindset features.

This is shown in the diagram below, which can be clicked to view full-size.

Notably, all of the green section is heightened in our condition.

Schadenfreude/jealousy (threat-proxy features)

On Neurology of the social mindset, I highlighted that episodic memories that trigger a brainstem response need not be those that resemble one’s own behaviours during episodes of the same response but rather can be anything (since anything can be witnessed at the time of a brainstem response). However, one’s own behaviours end up accumulating as the most significant triggers of a brainstem response, due to being exposed to them during every episode of the response.

However, in phenomena such as ‘schadenfreude’ or jealousy, the experience of a physically threatening human creates the episodic-memory nodes that later trigger this feeling. The formative episodes consist of a person posing a threat to an innate survival mechanism, such as causing or potentially causing physical harm or pain. In these instances, one’s brainstem response is one of pain or stress, while the phenomenon being witnessed is a person showing expressions of accomplishment or triumph. These become attached together by the social mindset. Likewise, when the threatening person is neutralised, one would experience responses of happiness and relief, while the formerly threatening person would show expressions of frustration or pain.

With the addition of the social mindset, this creates a new effect in which the perceived joy of a person/animal/etc. that is not an active threat to an innate survival mechanism can become a trigger for one’s frustration (envy/jealousy). Likewise, the perceived pain or frustration of a person/animal/etc. (including oneself) that is not an active threat to an innate survival mechanism can become a trigger for one’s own pleasure (schadenfreude). The strength of this effect depends on the frequency and spontaneity of threat perception in the individual, which is discussed in the next section.

Interactions with spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies

The threat-proxy features of the social mindset originate from experiences of dealing with a physical human threat, including the successful aftermath. Differences in frequency and spontaneity of threat perception in the individual therefore guide differences in the representation of the threat-proxy and non-threat-proxy social-mindset features in the person with the social mindset. These can sometimes be to the extent of pathological.

Disorders involving high, spontaneous threat perception, such as antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) or borderline personality disorder (BPD), have been linked to underdevelopment and hyperactivity of the amygdala with reduced authority of the prefrontal cortex (especially orbitofrontal/ventromedial) over the amygdala.[16][17][18][19][20][21] BPD has been noted for its symptomatic similarities to temporal-lobe epilepsy (the temporal lobe containing the amygdala), and similar spontaneous discharges have been observed in BPD.[22][23]

Combined with the social mindset and the effect described in the previous section, this can also result in a higher rate of feeling pleasure or reward (rather than no emotion or stress/anxiety) from the displeasure of non-threatening proxies, hence the higher rates of harming animals in ASPD[24] or the higher rates of self-harm in BPD.[25] This is also likely to be the explanation for social behaviours in psychopathy associated instead with hypoactivity of the amygdala, such as superficial charm, manipulation, pathological lying, stimulation seeking, callousness, juvenile delinquency and criminality.[26]

The correlation between this and sexual social-mindset associations is described in a later section.

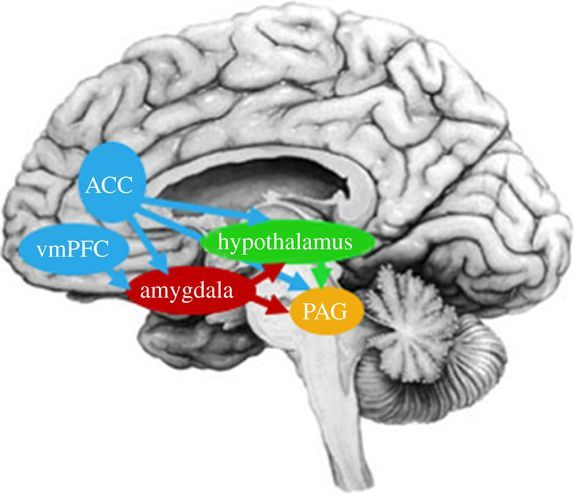

Interactions with sexual dimorphisms in aggression

Although there are some sexual dimorphisms in the structures of the social mindset (though mostly represented in the extremes), a large portion of the sexual dimorphism in social-mindset features stems from pre-human sexual dimorphisms in the aggression (and sexuality) network consisting of the amygdala, lateral septum, stria terminalis, hypothalamic nuclei and brainstem destinations such as the dorsal periaqueductal grey.[27]

Source: [28]. Licence: CC-BY-4.0.

Source: [29]. Licence: CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0.

The amygdala sends input to the hypothalamus via the stria terminalis,[30] while the lateral septum (at the base of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) inhibits the mediobasal hypothalamus,[31] which activates aggression through activation of the dorsal periaqueductal grey.[32]

The stria terminalis,[33] ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus[34] (in the mediobasal hypothalamus) and sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area of the hypothalamus[35] are roughly twice as large in males as in females.

In males, the higher aggression permitted by these structures allows the differential emotion between themselves and a physical human threat to more often become associated with the act of attacking – it is this that would more often provide reward when used on non-threatening proxies. This would explain the higher rates in males than females of social-mindset behaviours such as most crime,[36] sadism[37] and harming of animals for pleasure.[38]

In females, these structures do not permit as high external aggression, and as such, the differential emotion between themselves and a physical human threat would more often become associated with the act of complying – it is this that would more often provide reward when used on non-threatening proxies. This would explain the higher rates in females than males of social-mindset behaviours such as psychogenic self-harm[39] and anorexia nervosa.[40]

Sexual social-mindset associations

Sexual arousal, as a brainstem response, can also have social-mindset associations.

Sexually reproducing animals extend across phyla, so many non-social-mindset mechanisms have evolved to facilitate sexual arousal. In humans and many other vertebrates, the most significant one is sexual imprinting, created in the medial temporal lobe (or homologous region) during exposure to the family (or other conspecifics) in early childhood.[41]

The sight of anatomies that match these imprints serves as the trigger for the formative episodes for the social-mindset associations. As a result of the social mindset, anything that is witnessed at the time of sexual arousal during these episodes has the potential to serve as an episodic-memory trigger of arousal, especially with repeated experiences. Any trigger of sexual arousal that consists of a social-mindset feature or any other act or situation or imaginary scenario is created by the social mindset.

In the diagram, I have included many sexual social-mindset triggers to demonstrate the mechanism of sexual social-mindset associations, though some are uncommon or restricted to the spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies mentioned earlier, such as higher rates of self-harm materialising into higher rates of masochism in borderline personality disorder.[42]

The increase in year-round sexual arousal resulting from sexual social-mindset associations would have evolutionarily pressured the loss of the oestrous cycle. Bonobos, which have a basal social mindset, have sexual swellings that half the time do not correlate with their period of fertility.[43]

Attraction to breasts is a post-basal sexual social-mindset association. They are not universally covered or seen as sexualised in human cultures, such as many in Africa. The same is true for attraction to buttocks, which is only prevalent in Africa, the Middle East and the Americas.[44]

Interactions with spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies and sexual dimorphisms in aggression

Sexual social-mindset associations interact with both spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies and sexual dimorphisms in aggression.

In those with typical threat perception, non-threat proxies become sources of pleasure far more often than threat proxies. This means that there is more chance for an episode of sexual arousal to coincide with non-threat proxies being observed and having their associated features be added as a trigger for sexual attraction, such as altruism to others, care for pets or children, etc.

In those with high, spontaneous threat perception, significantly more threat proxies become sources of pleasure. This means that there is a much higher chance for an episode of sexual arousal to coincide with threat proxies being observed and having their associated features be added as a trigger for sexual arousal, such as harm to others, the self or animals.

In males with high, spontaneous threat perception, the higher aggression permitted by the hypothalamic network would result in a higher chance for an episode of sexual arousal to coincide with the threat proxy being dealt with by acts of aggression and having this be added as a trigger for sexual arousal, such as harm to others or animals, while in females with high, spontaneous threat perception, the lower aggression permitted by the hypothalamic network would result in a higher chance for an episode of sexual arousal to coincide with the threat proxy being dealt with by acts of compliance and having this be added as a trigger for sexual arousal, such as harm to the self.

Taboos

Taboos largely correlate with law and are a detached social-mindset feature.

Taboos and laws largely come about a result of the conflict between two populations within the social mindset: those with differences in the amygdala–hypothalamus network and those without.

Virtually all globally prevalent taboos/laws are consistent with the instigating factors being individuals with the social mindset with differences in the amygdala–septum–hypothalamus network:

- Many taboos and laws are for behaviours found in those with antisocial personality disorder (whose involvement of the social mindset and the amygdala is described earlier), such as violence or murder.

- As an inhibitor of the hypothalamic aggression centres, damage to the lateral septum, a set of nuclei at the base of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, in mice results in indiscriminate aggression known as ‘septal rage’.[45]

- The medial temporal lobe (especially the right medial temporal lobe) provides the visually imprinted contextual regulation for sexual arousal.[46] Klüver–Bucy syndrome, involving significant and often sex-/age-/relation-/species-indiscriminate hypersexual behaviour, is caused by damage to or removal of the medial temporal lobe close to or including the amygdala.[46][47][48] Other regions to result in hypersexuality when affected have included the hypothalamic and septal regions.[46]

- Homosexual males have been recorded to have a third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus that is smaller in size than that of heterosexual males and closer in size to that of females.[49]

- Paedophilic perpetrators have been recorded to have significantly decreased right amygdala, septum, bed-nucleus-of-stria-terminalis and hypothalamus volumes.[50]

- Kleine–Levin syndrome is a group of symptoms believed to result from hypothalamic dysfunction, often as a potential result of autoimmune activity following a viral respiratory infection. Symptoms of Kleine–Levin syndrome consist of week(s)-long episodes and include hypersexuality, especially in males, which has included homosexual, incestuous or paedophilic behaviour.[51][52]

This model posits that taboos (and laws) come about in a three-step process.

Innate initial factor

Like all detached social-mindset features, all taboos originate with an innate, non-social-mindset mechanism that is detached from the taboo as it exists now.

This mechanism involves some form of defensive or retaliatory aggression exhibited by an involved party. This is in the middle of the act or immediately after it, rather than later as a result of its long-term consequences (such as recessive genentic conditions from incest[53]), as both the act and the defensive aggression have to be visible together or in association as an episodic memory to initially appropriate the defensive aggression in association with the act.

- For murder, suicide or physical assault, the initial factor would have been the defensive aggression of an individual who was killed or attacked in perceived self-defence, as occurs in other animals.

- For adultery, the initial factor would have been the competitive aggression of an individual towards another individual disrupting access to their mate, whom they were sexually attracted to.

- For rape or sexual assault, the initial factor would have been the defensive aggression of an individual who was not sexually attracted to another individual making sexual advances on them, whose acts would therefore be treated as physical aggression.

- For paedophilia, the initial factor would have been both the hormonal mechanisms that result in prepubescent children not having significant sexual feelings until puberty and the statistical unlikelihood for a prepubescent child to be sexually attracted to an adult. As such, the above defensive aggression in response to an attempted sexual advance, especially by an adult, would have occurred very often in the child.

- For homosexuality (in the past in the West), the initial factor would have been the prevalent opposite-sex sexual imprinting that occurs in childhood among vertebrates. As such, due most people’s lack of attraction to someone of the same sex, the defensive aggression in response to an attempted sexual advance would have occurred often.

- For incest, the initial factor would have been the Westermarck effect, the effect in sexual imprinting responsible for the widespread lack of attraction siblings have for each other or their parents among vertebrates. As such, the defensive aggression in response to such an attempted sexual advance would have occurred very often.

- For bestiality, the initial factor would have been the sexual imprinting that results in attraction to conspecifics and not other species among vertebrates. The defensive aggression response would have occurred often from the animal towards the human (though also vice versa, leading to animal trials for bestiality).

Act (often threat-proxy-based)

For those with differences in the amygdala–hypothalamus network, many of the sources of innate aggression for those without these differences (such as sexual imprinting leading to incest aversion or lack of homosexual attraction) are now sources of pleasure or sexual arousal for them. Due to constituting a minority, this would have led their attempts of such acts to be statistically far less likely to be reciprocated.

In many cases, however, the mechanism described in Interactions with spontaneous-threat-perception pathologies also applies. This means that those with the social mindset who have high, spontaneous threat perception (also as a result of differences in the amygdala–hypothalamus network) turn expressions of displeasure into sources of pleasure/reward at a higher rate than others.

For certain examples, this now means that:

- For the displeasure of a person killed or attacked in self-defence, non-threats (threat proxies) can now also seen to provide this pleasure, meaning the person can kill or attack non-threats and receive the same pleasure/reward.

- For the displeasure of a person encountering a competitor to their mate, their displeasure can become a source of pleasure for the adulterer.

- For the displeasure of a person who is not sexually attracted to someone making sexual advances, their displeasure can become a source of pleasure for the rapist.

- For the displeasure of a prepubescent child in response to a sexual advance by an adult, their displeasure can become a source of pleasure for the paedophile.

These mechanisms create new sources of acts that result in defensive aggression in another individual, meaning that the acts dramatically increase in prevalence.

Empathy and attachment of the act (often threat-proxy-based) to the social mindset

The third step is the empathy the rest of those with the social mindset have for the victims of these unreciprocated acts, which are now mostly in the form of threat-proxy acts.

They relate the expressions of defensive aggression of the victims of these acts to episodic memories of their own defensive aggression, triggering their own defensive aggression. This results in them attaching the witnessed act as a triggering node of the defensive aggression, due to it having been witnessed at the same time.

This no longer binds their defensive aggression to the recipient of the act but now also to the act alone (or anything that resembles it), even in the absence of defensive aggression of the recipient or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

- For killing or attacking, the defensive aggression of the killed or attacked person is witnessed by another individual and triggers their defensive aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of killing or attacking becomes attached as a triggering node for defensive aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person killing or attacking (or anything that resembles it) can trigger defensive aggression alone, regardless of the recipient’s feelings at the time or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

This has most notably resulted in criminalisation of euthanasia and criminalisation of suicide. Although suicide is no longer criminalised in Western countries, those who are considered a ‘threat to themselves’ are subject to regulation or involuntary commitment.

- For a person encountering a competitor to their mate, the competitive aggression of the individual who lost the mate’s exclusive investment to the competitor is witnessed by another individual and triggers their aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of withdrawing exclusive investment in a mate to a competitor becomes attached as a triggering node for aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person withdrawing exclusive investment in a mate to a competitor alone (or anything that resembles it) can trigger defensive aggression, regardless of the recipient’s feelings at the time or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

The reason adultery has become less of a taboo/law over time (especially in the West) is due to the increase in the social group’s population and connectivity leading to a much higher rate of sexual encounters, dramatically lowering the threshold of normality for the number of potential partners one is expected to exclusively invest in when they meet. The active punishment or stigma for adultery is not the same as the celebration/happiness for marriage, which would derive from the empathy for the pleasure of those who are in love.

- For unwanted sexual advances, the defensive aggression of a person advanced on sexually by someone they were not attracted to is witnessed by another individual and triggers their defensive aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of an unwanted sexual advance becomes attached as a triggering node for defensive aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person committing anything that resembles an unwanted sexual advance can trigger defensive aggression alone, regardless of the recipient’s feelings at the time or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

This is also the origin of the sexual and genital taboo. In addition to this effect, the empathy for the recipients of the unwanted advances (their defensive aggression in association with acts towards their genitalia) resulted in appropriating their defensive aggression in association with their genitalia being available, leading to available genitalia itself becoming a source of aggression. In modern Western cultures, this extends to breasts.

Many swear words originated or acquired such status to refer to sex or genitalia specifically as this object of defensive aggression when visible, which became a separate concept as a result of the social mindset (similar to consciousness or free will), rather than sex or genitalia in general.

The intense societal aggression at anything that resembles an unwanted sexual advance also has the effect of coming back around to future recipients of similarly appearing but physically harmless acts, meaning that they themselves will appropriate this level of displeasure (especially after repeated exposure to the societal aggression in adulthood). This can lead to induced trauma that was not present at the time of the similarly appearing, physically harmless act that did not result in any defensive aggression at the time.

- For unwanted sexual advances on prepubescent children, the defensive aggression of the child advanced on sexually is witnessed by another individual and triggers their defensive aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of advancing sexually on a child becomes attached as a triggering node for defensive aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person advancing sexually on a child alone (or anything that resembles it) can trigger defensive aggression, regardless of the recipient’s feelings at the time or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

This taboo also has an age-gap effect that surpasses childhood and affects adulthood. This is due merely to the biological lesser likelihood for adult people of a large age gap to be reciprocally attracted to one another. This separates it from a phenomenon such as homosexuality, where the individuals involved (if neither heterosexual) are statistically more probable to have biologically reciprocal attraction.

As the global social group’s population and connectivity increased, the prepubescent or pubescent child’s statistically less probable attraction and more probable defensive aggression towards an adult individual’s sexual advances became a source of pleasure for adult threat-proxy-pursuing individuals more so than the far fewer instances that a child’s and adult’s reciprocal attraction were made societally visible. As such, laws against any potential sign of a sexual advance on a child became applied to increasingly higher ages of children, in an inverse effect to the taboo of homosexuality.

- For the prevalent lack of attraction people have to someone of the same sex, the defensive aggression of the heterosexual person advanced on sexually by someone of the same sex is witnessed by another individual and triggers their defensive aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of advancing sexually on someone of the same sex becomes attached as a triggering node for defensive aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person advancing sexually on someone of the same sex alone (or anything that resembles it) can trigger defensive aggression, regardless of the recipient’s feelings at the time or a recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

This taboo/law was reduced in the West, because as the social group’s population and connectivity increased, and it became far more likely for one homosexual individual to find another (rather than attempt to advance on heterosexual individuals), their statistically more probable reciprocal attraction and lack of defensive aggression became more societally visible.

- For the lack of attraction to other species, the defensive aggression of the animal advanced on sexually is witnessed by another individual and triggers their defensive aggression. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the act of advancing sexually on an animal becomes attached as a triggering node for defensive aggression.

This now means that the act or idea of a person advancing sexually on an animal alone (or anything that resembles it) can trigger defensive aggression, regardless of the animal recipient’s feelings at the time or an animal recipient at all. This defensive aggression later becomes appropriated among the social group and by each generation without having to witness the initial scenario.

This affects instances in which the animal instigated or was receptive of the act.

The reason the violence and sexuality taboos/laws (such as rape) remain biased against males is because of the way the hypothalamic sexual dimorphism in aggression discussed earlier played into the threat-proxy factor (step 2) of the formation of the taboo. In bonobos, which have a basal social mindset, females are known to band together to attack males who harass other females.[54]

The reason many of the taboos are sexual in nature and prohibit any form of unwanted tactile contact or even visual contact of a sexualised region, despite this not causing physical harm, is because sexual attraction would have been one of the few reasons a pre-human animal would have physically advanced on a conspecific and would have been one of the few possible sources, other than defensive aggression itself or cannibalism (which would have been less common), for defensive aggression to arise in the recipient.

For several of these taboos/laws, anything that superficially resembles the innate-aggression-inducing act is now a source of social defensive aggression in others, meaning even in cases in which there is no threat to survival in the recipient and no resultant defensive aggression, or the recipient is willing, the similarity of an act to other acts in which innate defensive aggression is caused, often intentionally (due to the threat-proxy mechanism), means that it is always treated with condemnation and punishment. This intense and progressively distorted social defensive aggression becomes appropriated by each generation.

This demonstrates the detachment effect of the social mindset as it affects taboos/laws.

This is a converse detachment effect to many other social-mindset features, in which the over-application is not with displeasure but rather pleasure, such as body modifications. With these, the act is seen as pleasurable even if it results in harm and goes against an innate survival centre.

Makeup and female fashion

The sexual dimorphism in aggression and sexuality is also responsible for the sexual dimorphism in facial cosmetics and fashion styles, which are detached social-mindset features.

At its origin, the formative episodes for makeup and female fashion styles would have been episodes of females observing a male select a receptive female to sexually advance on, due to facial and anatomical attraction as a result of sexual imprinting.

Once the male had sexually advanced on the receptive female, this would have resulted in both the male and the female showing expressions of pleasure. As a result of sexual arousal, the female’s lips and cheeks would have become flushed with blood.

Other receptive females would have observed the expressions of pleasure displayed by the male and female in association with the female’s facial appearance (both anatomical and the flushing as a result of sexual arousal) and bodily anatomy.

The expressions of pleasure would have resembled episodic memories of their own expressions of pleasure, which would have triggered the attached brainstem response. Due to having been witnessed at the same time, the female’s facial appearance and physical anatomy would have become added as a trigger of pleasure in the other females.

As such, to achieve this new trigger of pleasure, the females would have attempted to emulate the appearance of the successful female during her copulation with the male through whatever means, including by emulating the characteristics of her eyes or eyebrows, her facial flushing as a result of the sexual arousal and her body type.

Over time, females would have appropriated the cosmetics or clothing styles from other females without the need for the initial scenario, purely due to having seen their pleasure in association with the cosmetics/clothing style. With increasing size and connectivity of the social group, this effect would have grown substantially until a variety of artificial female cosmetic appearances were circulated among the social group.

This highlights the detachment effect of the social mindset as it affects makeup and female aesthetic clothing styles. The original, non-social reason for why the practice came about in its original form is forgotten, and a new, social reason (which is not subjectively comprehensible) is virtually all that remains.

Theism/spirituality or belief in a general ‘higher power’

Theism, spirituality or any belief in a general ‘higher power’ derives from relating the behaviours of natural events to episodic memories of one’s own behaviours, which triggers the associated brainstem response and results in the brainstem response characterising the natural events. This results in the natural events being seen as the manifestations of a being with the same brainstem responses (or emotions) the self has, similar to how another human or pet is seen. The simulation hypothesis is thus another form of this feature.

The effect is weaker than that of relating the behaviours and appearances of an animal or human to those of the self, due to the weaker resemblance. It is more so facilitated by a lack of other episodic memories to attach to the phenomenon (i.e. a lack of a known explanation) over the number of social-mindset-linked experiences to attach to the phenomenon.

In other words, it is stronger where the person has not had more experiences of witnessing or thinking about the events in association with these explanations than their own behaviours. Essentially, in the absence of another explanation and a vague resemblance to human behaviours, the phenomena are characterised as, ‘How would I feel if I were behaving like this?’

Prior to knowledge about natural phenomena such as weather, geology, astronomy or biology (such as childbirth), the primary source of characterisation for the phenomena was left to be one’s own behaviours and the attached brainstem responses, and as such, rich mythologies built around the phenomena.

Afterlife and soul

Belief in an afterlife, or that a dead person still has a ‘presence’, stems from the simple fact of the brainstem responses being attached to episodic memories of the dead person.

Since, despite the fact that the person is dead, one is still alive and one’s brainstem responses still active, the memories of the person can continue to trigger the brainstem responses and be characterised using those responses in the same way they did when they were triggered by witnessing the person while they were alive (such as facilitated empathy for the person).

This brainstem-response characterisation also serves as the basis of concepts such as ‘soul’, where the ‘body’ serves to represent everything about the person that is not characterised using the brainstem response.

Social interaction

The deity is believed to behave and respond like a human, i.e. it would return favours if it were treated well or return aggression if it were treated negatively. This is the origin of concepts such as ‘karma’ as well as prayer.

It is also the origin of prehistoric and historic concepts such as votive offerings and human and animal sacrifice. It was believed that, to receive good treatment from nature (seen as a being with human emotions), one should visibly show it respect, as one would a human, or offer it resources that humans could benefit from, such as an animal or human (in which prisoners or slaves were often used[55]).

Moral dualism

For beneficial events or individuals, in the relative absence of episodic memories of an explanation as to why or how the event or person was able to bring about such a beneficial effect, it is believed that nature made the event (or the person’s behaviour) happen for a reason similar to one that one would have oneself (such as generosity or love).

In the past, this occurred with fruitful harvests, victories in war or influential founders or rulers of kingdoms. In line with the mechanism, the deification of a person is not necessarily absolute but rather a spectrum of intensity, depending on how much their behaviour and effect could not be associated with episodic memories of an explanation and appeared massive enough to parallel the effects of natural events.

Similarly, for harmful events or individuals, in the relative absence of episodic memories of an explanation for their behaviour, it is believed that nature made the event (or the person’s behaviour) happen for a reason similar to one that one would have oneself (such as a desire to punish). This serves as the origin for individuals considered to be ‘possessed by the devil’.

Such language of ‘battling demons’ continues to be used for persons who exhibit harmful behaviour due to a mental condition.[56]

Fiction

Fiction is defined as either ‘literature … that describes imaginary events and people’ or ‘something that is invented or untrue’.[57]

As described on Neurology of the social mindset, the social mindset allows episodic memories to trigger emotional brainstem responses and reward directly.

Episodic memories are stored together according to commonalities to make predictions about phenomena. When something is witnessed that resembles the social-mindset-linked episodic memories, it triggers their associated brainstem responses and becomes added as a new episodic-memory node of the social mindset.

The social mindset thus allows for the possibility of a pursuit of fiction, or reward directly from either thinking about or witnessing imaginary concepts that resemble social-mindset-linked episodic memories, which causes them to trigger the brainstem response. It also allows for reward from nostalgia, or reward from thinking of episodic memories of events one experienced in the past (or witnessing stimuli that trigger these episodic memories), which causes them to trigger the associated brainstem responses.

As described in the Mechanism section of Neurology of the social mindset, most of the social-mindset nodes (though not all) are episodic memories of one’s own behaviours while an emotional brainstem response was occurring and are linked with episodic memories of similar behaviours/appearances in others. This gives rise to the predominance of anthropomorphisation in fictional media, an abundance of fiction about human figures and anthropomorphised animals or beings.

Unconscious thought appropriation

As described on Neurology of the social mindset, the social mindset arises from a feedback link from the brainstem to the medial prefrontal cortex.

As such, in comparison to the lack of the social mindset, the social mindset does not involve any additional cognition to occur; once a match is made to an episodic memory in a chain that links down to the anterior insular brainstem signature, the brainstem response is triggered automatically and characterises what is seen automatically and uncontrollably, without any meaningful ability to stop it in the moment. The link is instant and not effortful, and its presence is not voluntary.

As represented by many of its features, the social mindset thus results in an unconscious thought-appropriation mechanism by which the behaviours and practices of other humans can be appropriated as one’s own behaviours, purely due to seeing expressions of pleasure or displeasure in association with them, which trigger one’s own feelings of pleasure or displeasure.

Essentially, in addition to the innate survival mechanisms such as satiety or pain avoidance regulating reward/aversion, the feedback mechanism now also regulates reward/aversion.

Instead of thoughts being solely geared towards individual survival, humans (or non-humans) showing expressions of a certain emotion in association with a certain practice can lead to the memory of this external practice being added as a new source of reward/aversion.

This results in a constant gradual replacement of sources of reward/aversion with externally witnessed episodic memories, sources that progressively do not correspond to the satiety/pain avoidance centres that remain in the individual.

In essence, a significant portion of an individual’s thoughts, desires and aversions are now those of many other people, and the individual is significantly sacrificed. This is similar to the behaviour of a cell in a multicellular organism, behaviour that is dynamically changing (in response to signals from other cells) and often self-detrimental and other-serving, as opposed to the consistent, self-serving activity of a unicellular organism.

Lack of subjective awareness

Because these new, external sources of reward/aversion are now one’s own sources of reward/aversion and trigger the same reward/aversion centres, from the person’s point of view, they are their own thoughts.

It cannot be subjectively comprehended that they were acquired unconsciously from someone else, since they become what constitutes reward/aversion and guides behaviour in that person rather than merely being regulators of innate sources of reward/aversion.

In other words, they become what perspective is built around rather than being the perspective that is built around the person’s innate survival mechanisms. This is part of the basis of the term ‘social mindset‘.

The reason for the appropriated behaviour being a source of reward/aversion will typically either itself have been appropriated, will be confabulated or will default to ‘I just like it’/’I just don’t like it’/’It’s just wrong’/’I don’t know’/etc.

As a result of the mechanism, it also cannot be comprehended that the same mechanism is occurring in others with the social mindset, since the person will compare the behaviours of others to episodic memories of their own behaviours and trigger the associated brainstem response, which will characterise the person.

As a result, people will be characterised as if they were oneself and have the socially appropriated thoughts and desires the self has, which one is not aware were socially appropriated. They will be characterised as having the feeling of free will and choice that results from one’s own social mindset.

As such, everyone will be considered an ‘individual’, even though many of their own thoughts were appropriated via the mechanism; they will be considered as such because one considers oneself an individual, even though many of one’s own thoughts were also appropriated via the mechanism.

Although objectively, those with the social mindset become extremely similar among the social group as they appropriate behaviours and practices from others as their own, this is not easily cognised by themselves or others with the social mindset, as it is overruled by the ‘individuality’ characterisation created by the social mindset.

This lack of subjective awareness also affects characterisation of phenomena that resemble the behaviours of humans but lack the human social mindset, such as other humans with certain neurological conditions such as severe autism spectrum disorder, pets/other animals and sometimes nature/the universe.

When the behaviours/appearances of these phenomena resemble episodic memories attached to certain brainstem responses in oneself, they will automatically be characterised as having the emotions or desires that these episodic memories correlate to in the self (many of which were unconsciously appropriated from other humans), despite the fact that they they do not, and there will be no way to dispel this false characterisation in the moment, since it is the product of an inherent mechanism of the human brain.

Lack of representation of the mechanism in research

Due to the inability to comprehend the mechanism when one has it, it is conspicuously omitted or avoided in almost all explanations of features such as language, addiction to drugs or religion.

The focus is placed on other mechanisms that are contributory, such as Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area or FOXP2 in language, the dopaminergic system in recreational drug use, the fusiform face area,[58] arcuate fasciculus[59] or neuroinflammation[60] in autism and childhood upbringing in mental disorders of self-esteem,[61] with a ‘missing link’ that, despite not being present in most other animals, goes either unnoticed and unquestioned or leaves heads scratching.

One article notes how the study of consciousness garnered a ‘taboo’ in the 20th century,[62] and the study of the origin of language was banned by the Linguistic Society of Paris in 1866.[63]

These are not taboos in the technical sense. Rather, this undue avoidance of the study of the mechanism is a result of the mechanism itself guiding human behaviour and goals.

To study the social-mindset mechanism directly conflicts with the humans’ subjective reasoning for the content of the study (such as why they consider themselves to have the features), while to study subjects separate to the mechanism, such as physics, maths and computing, does not conflict with the humans’ subjective reasoning for the content of the study (such as why 1 + 1 = 2).

This also leads the study of these other subjects to receive far more attention and gain far more esteem than those closer to the mechanism, such as neuroscience, genetics or anthropology, leading figures such as Albert Einstein or Isaac Newton to become metaphors of intelligence, while figures in these other fields go unknown.

Creation of problems of consciousness and free will

With the social mindset, problems of consciousness, qualia, mind and body, agency, free will and intent are artificially created, because brainstem responses correlating to episodic memories are used to characterise both one’s own behaviour and that of other individuals. These concepts are now created, garner their own existence outside the individual and become debated as external concepts. Similar problems of ‘sentience’, including that of artificial intelligence, are also created.

It leads concepts such as determinism, which would otherwise be the default or initial position, given atomic, molecular and cellular cause-and-effect per states of energy, to be a minority[64] or partial[65] viewpoint, similar to the case with atheism.

Such debates are a result of falling foul to the illusions the social mindset creates. The social-mindset mechanism that supposedly makes humans special merely consists of a small connection between the brainstem and medial prefrontal cortex, which forms a loop in which episodic memories previously associated with an innate reward/aversion now also directly trigger reward/aversion, and brainstem responses characterise external phenomena.

This is a simple physical and material effect, and as such, there is little materially separating an animal’s brain or a computer from a human’s brain.

Other features

There are other features I have not yet described that require the involvement of the social mindset, including, but not limited to:

- ‘Comfort eating’, formed by episodically associating the act of eating food or witnessing someone’s pleasure with food with the pleasure resulting from satiety fulfilment rather than the satiety fulfilment itself. The appetite-stimulant hormones ghrelin[66][67] and orexin[68] are low in obese individuals, and the appetite-inhibitor hormone leptin is high,[68] but ghrelin is high in the obesity-associated genetic disorder Prader–Willi syndrome.[69][70] This holds responsibility for the psychogenic obesity ‘epidemic’.

- The ability to consider sleep something to ‘love’ instead of something that the body simply forces one to do when it needs it (and the resultant napping culture), formed by the same mechanism as above

- Adoption of regular caffeine use and caffeine culture, formed by the same mechanism as adoption of recreational drug use

- Gender identities, formed by the relation of another sex’s (or gender identity’s) interests or behaviours to one’s own behaviours and associated brainstem responses to a significant degree (including behaviours created by the social mindset, such as makeup)

- Cuteness, formed by episodically associating one’s behaviours when one was helpless (typically when one was an infant or young child) with the associated brainstem responses, resulting in these responses being triggered by and characterising anything that resembles these behaviours, such as a baby or small animal, leading to a desire to help it as if it were helpless and wanted help. This also leads to the creation of ‘baby-talk‘ and ‘pet-talk‘, which represent a similar form of speech or babbling to that used when one was an infant or young child.

- Language of ‘battling’ an illness (such as cancer) as if the illness were another human, formed by a similar mechanism to that described for theism above

- Social-trend adoption, formed by the basic mechanism of empathy for a positive feeling (seen in association with the social trend)

References

- ^ Anderson, James R.; Gallup, Gordon G (2015-10-01). "Mirror self-recognition: a review and critique of attempts to promote and engineer self-recognition in primates". Primates. 56 (4): 317–326. doi:10.1007/s10329-015-0488-9. ISSN 1610-7365.

- ^ Demuru, Elisa; Palagi, Elisabetta (2012-11-14). "In Bonobos Yawn Contagion Is Higher among Kin and Friends". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49613. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049613. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ^ Palagi, E.; Leone, A.; Mancini, G.; Ferrari, P. F (2009-11-17). "Contagious yawning in gelada baboons as a possible expression of empathy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (46): 19262–19267. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910891106. ISSN 0027-8424, 1091-6490. PMID 19889980.

- ^ Rajecki, D. W (2014-05-22). "Comparing Behavior: Studying Man Studying Animals".

- ^ Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Irenaus (2017-07-05). "Love and Hate: The Natural History of Behavior Patterns".

- ^ Palagi, Elisabetta; Norscia, Ivan (2013-11-05). "Bonobos Protect and Console Friends and Kin". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e79290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079290. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ^ a b Manson, Joseph H.; Perry, Susan; Parish, Amy R (1997-10-01). "Nonconceptive Sexual Behavior in Bonobos and Capuchins". International Journal of Primatology. 18 (5): 767–786. doi:10.1023/A:1026395829818. ISSN 1573-8604.

- ^ Waal, Frans B. M. de (1995-03). "Bonobo Sex and Society". Scientific American. 272 (3): 82-88. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0395-82. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ a b Clay, Zanna; Pika, Simone; Gruber, Thibaud; Zuberbühler, Klaus (2011-08-23). "Female bonobos use copulation calls as social signals". Biology Letters. 7 (4): 513–516. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.1227.

- ^ Brewer, Gayle; Hendrie, Colin A (2011-06-01). "Evidence to Suggest that Copulatory Vocalizations in Women Are Not a Reflexive Consequence of Orgasm". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 40 (3): 559–564. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9632-1. ISSN 1573-2800.

- ^ Kaighobadi, Farnaz; Shackelford, Todd K.; Weekes-Shackelford, Viviana A (2012-10). "Do Women Pretend Orgasm to Retain a Mate?" Archives of sexual behavior. 41 (5): 1121–1125. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9874-6. ISSN 0004-0002. PMC 3563256. PMID 22089325.

- ^ Miklósi, Ádam; Soproni, Krisztina (2006-04-01). "A comparative analysis of animals' understanding of the human pointing gesture". Animal Cognition. Springer Link. 9 (2): 81–93. doi:10.1007/s10071-005-0008-1. ISSN 1435-9456.

- ^ a b Zald, David H.; Zatorre, Robert J.; Gottfried, Jay A (2011). "Music". PMID 22593901.

- ^ Haesler, Sebastian; Wada, Kazuhiro; Nshdejan, A.; Morrisey, Edward E.; Lints, Thierry; Jarvis, Eric D.; Scharff, Constance (2004-03-31). "FoxP2 Expression in Avian Vocal Learners and Non-Learners". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (13): 3164–3175. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4369-03.2004. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6730012. PMID 15056696.

- ^ Clovis, Yoanne M.; Enard, Wolfgang; Marinaro, Federica; Huttner, Wieland B.; Tonelli, Davide De Pietri (2012-09-15). "Convergent repression of Foxp2 3′UTR by miR-9 and miR-132 in embryonic mouse neocortex: implications for radial migration of neurons". Development. 139 (18): 3332–3342. doi:10.1242/dev.078063. ISSN 0950-1991, 1477-9129. PMID 22874921.

- ^ Yang, Yaling; Raine, Adrian; Lencz, Todd; Bihrle, Susan; LaCasse, Lori; Colletti, Patrick (2005-05-15). "Volume Reduction in Prefrontal Gray Matter in Unsuccessful Criminal Psychopaths". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (10): 1103–1108. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.021. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ^ Yang, Yaling; Raine, Adrian; Colletti, Patrick; Toga, Arthur W.; Narr, Katherine L (2010-08). "Morphological alterations in the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala in unsuccessful psychopaths". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 119 (3): 546–554. doi:10.1037/a0019611. ISSN 1939-1846. PMID 20677843.

- ^ Donegan, Nelson H; Sanislow, Charles A; Blumberg, Hilary P; Fulbright, Robert K; Lacadie, Cheryl; Skudlarski, Pawel; Gore, John C; Olson, Ingrid R; McGlashan, Thomas H; Wexler, Bruce E (2003-12-01). "Amygdala hyperreactivity in borderline personality disorder: implications for emotional dysregulation". Biological Psychiatry. 54 (11): 1284–1293. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00636-X. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ^ New, Antonia S.; Hazlett, Erin A.; Buchsbaum, Monte S.; Goodman, Marianne; Mitelman, Serge A.; Newmark, Randall; Trisdorfer, Roanna; Haznedar, M. Mehmet; Koenigsberg, Harold W.; Flory, Janine; Siever, Larry J (2007-07). "Amygdala–Prefrontal Disconnection in Borderline Personality Disorder". Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (7): 1629–1640. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301283. ISSN 1740-634X.

- ^ Soloff, Paul H.; Meltzer, Carolyn Cidis; Becker, Carl; Greer, Phil J.; Kelly, Thomas M.; Constantine, Doreen (2003-07-30). "Impulsivity and prefrontal hypometabolism in borderline personality disorder". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 123 (3): 153–163. doi:10.1016/S0925-4927(03)00064-7. ISSN 0925-4927.

- ^ Boccardi, Marina; Frisoni, Giovanni B.; Hare, Robert D.; Cavedo, Enrica; Najt, Pablo; Pievani, Michela; Rasser, Paul E.; Laakso, Mikko P.; Aronen, Hannu J.; Repo-Tiihonen, Eila; Vaurio, Olli; Thompson, Paul M.; Tiihonen, Jari (2011-08-30). "Cortex and amygdala morphology in psychopathy". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 193 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.013. ISSN 0925-4927.

- ^ Harris, Catherine L.; Dinn, Wayne M.; Marcinkiewicz, Jonathan A (2002-10-01). "Partial seizure-like symptoms in borderline personality disorder". Epilepsy & Behavior. 3 (5): 433–438. doi:10.1016/S1525-5050(02)00521-8. ISSN 1525-5050.

- ^ Boutros, Nashaat N.; Torello, Michael; McGlashan, Thomas H (2003-05). "Electrophysiological Aberrations in Borderline Personality Disorder: State of the Evidence". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 15 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1176/jnp.15.2.145. ISSN 0895-0172, 1545-7222.

- ^ Gleyzer, Roman; Felthous, Alan R.; Holzer, Charles E (2002). "Animal cruelty and psychiatric disorders". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 30 (2): 257–265. ISSN 1093-6793. PMID 12108563.

- ^ Sansone, Randy A.; Wiederman, Michael W.; Sansone, Lori A (1998-11). "The self-harm inventory (SHI): Development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 54 (7): 973-983. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199811)54:7<973::aid-jclp11>3.0.co;2-h. ISSN 0021-9762, 1097-4679.

- ^ Glenn, A. L.; Raine, A.; Schug, R. A (2009-01). "The neural correlates of moral decision-making in psychopathy". Molecular Psychiatry. 14 (1): 5–6. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.104. ISSN 1476-5578.

- ^ Yang, Cindy F.; Chiang, Michael; Gray, Daniel C.; Prabhakaran, Mahalakshmi; Alvarado, Maricruz; Juntti, Scott A.; Unger, Elizabeth K.; Wells, James A.; Shah, Nirao M (2013-05-09). "Sexually dimorphic neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus govern mating in both sexes and aggression in males". Cell. 153 (4): 896–909. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.017. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 3767768. PMID 23663785.

- ^ Roelofs, Karin (2017-04-19). "Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. royalsocietypublishing.org (Atypon). 372 (1718): 20160206. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0206. (Image cropped by myself.)

- ^ Loonen, Anton J. M.; Ivanova, Svetlana A (2019/04). "Evolution of circuits regulating pleasure and happiness with the habenula in control". CNS Spectrums. Cambridge University Press. 24 (2): 233–238. doi:10.1017/S1092852917000748. ISSN 1092-8529, 2165-6509.

- ^ Gouveia, Flavia Venetucci; Hamani, Clement; Fonoff, Erich Talamoni; Brentani, Helena; Alho, Eduardo Joaquim Lopes; de Morais, Rosa Magaly Campêlo Borba; de Souza, Aline Luz; Rigonatti, Sérgio Paulo; Martinez, Raquel C. R (2019-07-01). "Amygdala and Hypothalamus: Historical Overview With Focus on Aggression". Neurosurgery. 85 (1): 11–30. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyy635. ISSN 0148-396X.

- ^ Aleyasin, Hossein; Flanigan, Meghan; Russo, Scott J (2018-4). "Neurocircuitry of aggression and aggression seeking behavior: Nose poking into brain circuitry controlling aggression". Current opinion in neurobiology. 49: 184–191. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.013. ISSN 0959-4388. PMC 5935264. PMID 29524848.

- ^ Haller, József (2018-06-08). "The Role of the Lateral Hypothalamus in Violent Intraspecific Aggression—The Glucocorticoid Deficit Hypothesis". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 12. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2018.00026. ISSN 1662-5137. PMC 6002688. PMID 29937719.

- ^ Swaab, Dick F (2007-09-01). "Sexual differentiation of the brain and behavior". Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 21 (3): 431–444. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2007.04.003. ISSN 1521-690X.

- ^ Zuloaga, Damian G.; Puts, David A.; Jordan, Cynthia L.; Breedlove, S. Marc (2008-5). "The Role of Androgen Receptors in the Masculinization of Brain and Behavior: What we’ve learned from the Testicular Feminization Mutation". Hormones and behavior. 53 (5): 613–626. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.01.013. ISSN 0018-506X. PMC 2706155. PMID 18374335.

- ^ Hofman, M A; Swaab, D F (1989-06). "The sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in the human brain: a comparative morphometric study." Journal of Anatomy. 164: 55–72. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1256598. PMID 2606795.

- ^ "Table 66 – Crime in the United States". FBI. 2011. (Archive version from 20 October 2020.)

- ^ "Bondage-Discipline, Dominance-Submission and Sadomasochism (BDSM) From an Integrative Biopsychosocial Perspective: A Systematic Review". Sexual Medicine. 2019-06-01. 7 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2019.02.002. ISSN 2050-1161.

- ^ Dadds, Mark R.; Whiting, Clare; Bunn, Paul; Fraser, Jennifer A.; Charlson, Juliana H.; Pirola-Merlo, Andrew (2004-06-01). "Measurement of Cruelty in Children: The Cruelty to Animals Inventory". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 32 (3): 321–334. doi:10.1023/B:JACP.0000026145.69556.d9. ISSN 1573-2835.

- ^ Hawton, Keith; Saunders, Kate EA; O'Connor, Rory C (2012-06-23). "Self-harm and suicide in adolescents". The Lancet. 379 (9834): 2373–2382. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. ISSN 0140-6736, 1474-547X. PMID 22726518.

- ^ Smink, Frédérique R. E.; van Hoeken, Daphne; Hoek, Hans W (2012-8). "Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (4): 406–414. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. ISSN 1523-3812. PMC 3409365. PMID 22644309.

- ^ Marcinkowska, Urszula M; Rantala, Markus J (2012-07-01). "Sexual Imprinting on Facial Traits of Opposite-Sex Parents in Humans". Evolutionary Psychology. 10 (3): 147470491201000318. doi:10.1177/147470491201000318. ISSN 1474-7049.

- ^ Frías, Álvaro; González, Laura; Palma, Cárol; Farriols, Núria (2017-04-01). "Is There a Relationship Between Borderline Personality Disorder and Sexual Masochism in Women?" Archives of Sexual Behavior. 46 (3): 747–754. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0834-z. ISSN 1573-2800.

- ^ Douglas, Pamela Heidi; Hohmann, Gottfried; Murtagh, Róisín; Thiessen-Bock, Robyn; Deschner, Tobias (2016-06-30). "Mixed messages: wild female bonobos show high variability in the timing of ovulation in relation to sexual swelling patterns". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0691-3. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4928307. PMID 27356506.

- ^ "Which countries prefer butts to boobs?" The Daily Dot. 2014-12-12. (Archive version from 17 October 2019.)

- ^ Gotsick, James E.; Marshall, Roger C (1972-10-01). "Time course of the septal rage syndrome". Physiology & Behavior. 9 (4): 685–687. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(72)90033-9. ISSN 0031-9384.

- ^ a b c Mendez, Mario F.; Chow, Tiffany; Ringman, John; Twitchell, Geoff; Hinkin, Charles H (2000-02-01). "Pedophilia and Temporal Lobe Disturbances". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 12 (1): 71–76. doi:10.1176/jnp.12.1.71. ISSN 0895-0172.

- ^ M Das, Joe; Siddiqui, Waquar (2020). "Kluver Bucy Syndrome". PMID 31334941.

- ^ Hayman, L. Anne; Rexer, Jennie L.; Pavol, Marykay A.; Strite, Daniel; Meyers, Christina A (1998-08-01). "Klüver-Bucy Syndrome After Bilateral Selective Damage of Amygdala and Its Cortical Connections". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 10 (3): 354–358. doi:10.1176/jnp.10.3.354. ISSN 0895-0172.

- ^ LeVay, S (1991-08-30). "A difference in hypothalamic structure between heterosexual and homosexual men". Science (New York, N.Y.). 253 (5023): 1034–1037. doi:10.1126/science.1887219. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 1887219.

- ^ Schiltz, Kolja; Witzel, Joachim; Northoff, Georg; Zierhut, Kathrin; Gubka, Udo; Fellmann, Hermann; Kaufmann, Jörn; Tempelmann, Claus; Wiebking, Christine; Bogerts, Bernhard (2007-06-01). "Brain Pathology in Pedophilic Offenders: Evidence of Volume Reduction in the Right Amygdala and Related Diencephalic Structures". Archives of General Psychiatry. 64 (6): 737–746. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.737. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ^ Ramdurg, Santosh (2010). "Kleine–Levin syndrome: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment". Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 13 (4): 241–246. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.74185. ISSN 0972-2327. PMC 3021925. PMID 21264130.

- ^ Miglis, Mitchell G; Guilleminault, Christian (2014-01-20). "Kleine-Levin syndrome: a review". Nature and Science of Sleep. 6: 19–26. doi:10.2147/NSS.S44750. ISSN 1179-1608. PMC 3901778. PMID 24470783.

- ^ Hamamy, Hanan (2012-7). "Consanguineous marriages". Journal of Community Genetics. PubMed Central. 3 (3): 185–192. doi:10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y. ISSN 1868-310X. PMC 3419292. PMID 22109912.

- ^ Tokuyama, Nahoko; Furuichi, Takeshi (2016-09-01). "Do friends help each other? Patterns of female coalition formation in wild bonobos at Wamba". Animal Behaviour. 119: 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.06.021. ISSN 0003-3472.

- ^ Durán, Diego (1971). "Book of the gods and rites and the ancient calendar."

- ^ Sisti, Dominic; Segal, Andrea (2014-08-26). "Battling demons? When it comes to mental illness, language matters". The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Archive version from 27 October 2020.)

- ^ "Fiction | Definition of Fiction by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Fiction". Lexico Dictionaries | English. (Archive version from 6 August 2020.)

- ^ Hadjikhani, Nouchine; Joseph, Robert M.; Snyder, Josh; Chabris, Christopher F.; Clark, Jill; Steele, Shelly; McGrath, Lauren; Vangel, Mark; Aharon, Itzhak; Feczko, Eric; Harris, Gordon J.; Tager-Flusberg, Helen (2004-07). "Activation of the fusiform gyrus when individuals with autism spectrum disorder view faces". NeuroImage. 22 (3): 1141–1150. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.025. ISSN 1053-8119. PMID 15219586.

- ^ Moseley, Rachel L.; Correia, Marta M.; Baron-Cohen, Simon; Shtyrov, Yury; Pulvermüller, Friedemann; Mohr, Bettina (2016). "Reduced Volume of the Arcuate Fasciculus in Adults with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Conditions". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 10: 214. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00214. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 4867673. PMID 27242478.

- ^ Siniscalco, Dario; Schultz, Stephen; Brigida, Anna Lisa; Antonucci, Nicola (2018-06-04). "Inflammation and Neuro-Immune Dysregulations in Autism Spectrum Disorders". Pharmaceuticals. 11 (2). doi:10.3390/ph11020056. ISSN 1424-8247. PMC 6027314. PMID 29867038.

- ^ Leichsenring, Falk; Leibing, Eric; Kruse, Johannes; New, Antonia S.; Leweke, Frank (2011-01-01). "Borderline personality disorder". The Lancet. 377 (9759): 74–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5. ISSN 0140-6736, 1474-547X. PMID 21195251.

- ^ Goff, Philip (2019-11-01). "Science as we know it can't explain consciousness – but a revolution is coming". The Conversation. (Archive version from 27 July 2020.)

- ^ Hauser, Marc D.; Yang, Charles; Berwick, Robert C.; Tattersall, Ian; Ryan, Michael J.; Watumull, Jeffrey; Chomsky, Noam; Lewontin, Richard C (2014-05-07). "The mystery of language evolution". Frontiers in Psychology. PubMed Central. 5. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00401. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 4019876. PMID 24847300.

- ^ Stix, Gary (2015-01-15). "Site Survey Shows 60 Percent Think Free Will Exists. Read Why". Scientific American Blog Network. (Archive version from 8 December 2019.)

- ^ Bourget, David; Chalmers, David J (2014-09-01). "What do philosophers believe?" Philosophical Studies. 170 (3): 465–500. doi:10.1007/s11098-013-0259-7. ISSN 1573-0883.

- ^ Tschöp, Matthias; Weyer, Christian; Tataranni, P. Antonio; Devanarayan, Viswanath; Ravussin, Eric; Heiman, Mark L (2001-04-01). "Circulating Ghrelin Levels Are Decreased in Human Obesity". Diabetes. 50 (4): 707–709. doi:10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707. ISSN 0012-1797, 1939-327X. PMID 11289032.

- ^ Shiiya, Tomomi; Nakazato, Masamitsu; Mizuta, Masanari; Date, Yukari; Mondal, Muhtashan S.; Tanaka, Muneki; Nozoe, Shin-Ichi; Hosoda, Hiroshi; Kangawa, Kenji; Matsukura, Shigeru (2002-01-01). "Plasma Ghrelin Levels in Lean and Obese Humans and the Effect of Glucose on Ghrelin Secretion". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 87 (1): 240–244. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.1.8129. ISSN 0021-972X.

- ^ a b Adam, J. A.; Menheere, Ppca; van Dielen, FMH; Soeters, P. B.; Buurman, W. A.; Greve, J. W. M (2002-02). "Decreased plasma orexin-A levels in obese individuals". International Journal of Obesity. 26 (2): 274–276. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801868. ISSN 1476-5497.

- ^ Goldstone, Anthony P.; Thomas, E. Louise; Brynes, Audrey E.; Castroman, Gabriela; Edwards, Ray; Ghatei, Mohammad A.; Frost, Gary; Holland, Anthony J.; Grossman, Ashley B.; Korbonits, Márta; Bloom, Stephen R.; Bell, Jimmy D (2004-04-01). "Elevated Fasting Plasma Ghrelin in Prader-Willi Syndrome Adults Is Not Solely Explained by Their Reduced Visceral Adiposity and Insulin Resistance". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. academic.oup.com. 89 (4): 1718–1726. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031118. ISSN 0021-972X.

- ^ DelParigi, Angelo; Tschöp, Matthias; Heiman, Mark L.; Salbe, Arline D.; Vozarova, Barbora; Sell, Susan M.; Bunt, Joy C.; Tataranni, P. Antonio (2002-12-01). "High Circulating Ghrelin: A Potential Cause for Hyperphagia and Obesity in Prader-Willi Syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. academic.oup.com. 87 (12): 5461–5464. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-020871. ISSN 0021-972X.

- ^ Demuru, Elisa; Palagi, Elisabetta (2012-11-14). "In Bonobos Yawn Contagion Is Higher among Kin and Friends". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49613. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049613. ISSN 1932-6203.